Patients make appointments to see their primary care physician when a health issue arises, but often more complex cases merit referral to a specialist. Presenting with a wide range of symptoms, patients with atypical HUS often are referred by their primary care doctor to a physician with special medical training in areas such as: nephrology (kidney or renal diseases), hematology (blood disorders), immunology (immune issues, to include the complement system), or other specialty areas (oncology or hem-onc for example). Patients experiencing their first episode of aHUS activity may be assigned to a specialist based on generalized guidelines specific to their hospital or physician’s medical practice.

Is there a case to be made for cross-specialty collaboration to improve patient care and better outcomes?

What would a collaborative approach aHUS patient care entail? Should the basics of physician education broaden to include heightened awareness of thrombotic microangiopathies and the need for multidisciplinary approaches to patient care?

What role might patients play as translational medicine builds on basic research advances and the boom in genomics, biotech, and other fields to develop new therapies or medical diagnostics within a collaborative, multi-disciplinary ‘bench to bedside’ approach?

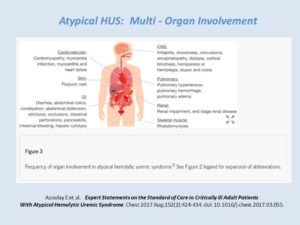

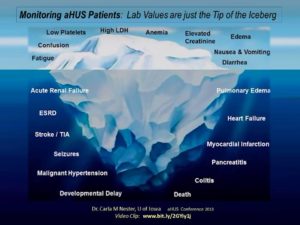

Diagnosis of aHUS can be very difficult as the initial vague symptoms can quickly become urgent, but those medical symptoms are common to many different other health conditions or diseases. Patients with atypical HUS most often have: blood and blood vessels which are affected, red blood cell counts that are low (anemia), a drop in platelet counts (used in clotting, thrombocytopenia is too few platelets) and tiny clots which may form anywhere in the body but often affect the kidneys and brain. Development of tiny clots (thrombi) can happen in different parts of the body to cause sudden or life-threatening conditions such as seizures, vision loss, stroke, cardiac issues, kidney failure and other serious medical situations. Atypical HUS can impact any organ or body system, which may cause a complex patient profile that requires a degree of consultation with physicians in other specialties. Activation of complement pathways and its dysregulation, a hallmark of aHUS activity, plays a central role in many diseases. Research done for other complement-mediated diseases, or those with similar underlying mechanisms, may provide knowledge to advance aHUS research and therapeutic drug discovery. There’s a current trend toward connectivity in research for associated diseases, fostered by improved insight into immune cross-talk mechanisms. Our aHUS Alliance January 2017 article on aHUS Theraputic Drug R & D ends with such a list of various complement-mediated, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases. (Click to view for our 2020 aHUS Therapeutic Drug Overview)

Patient care can be very complex when there is overlap, or when another disease state must be treated at the same time. Sometimes thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs) are induced by or happen with an underlying medical condition such as cancer or autoimmune disorders (with aHUS secondary to SLE or lupus nephritis), or it may occur after stem-cell (HSCT) or organ transplantation (TA-TMA). ‘Secondary TMAs’ might trigger due to infections, be associated with pregnancy or delivery, or become activated by certain drugs, understandably with treatment needs focused on the cause or background disease. Genetic testing in the future may advance and expand to provide additional insight and information in this area. In some cases of atypical HUS, organs other than the kidneys might be most impacted. The term ‘extra renal involvement’ indicates disease activity that may affect organs other than kidneys, such as heart, lungs, GI tract, eyes, skin, or brain). The Global aHUS Patient Registry reported that extra renal manifestations (problems elsewhere than the kidneys) occur more often in adults than children, and that 6 months prior to enrollment in the Global aHUS Patient Registry, “renal manifestations were reported in 34%, gastrointestinal in 18%, cardiovascular in 15%, central nervous system in 11%, and pulmonary in 9%.” This can make diagnosis of atypical HUS even more complicated, as physicians may encounter challenges when attempting to piece together facts and gain an accurate view of diagnosis and treatment.

Atypical HUS can no longer just be called a ‘kidney disease’. In a case study titled An Atypical Case of Atypical HUS (deYao et al, 2015) it was noted that 20% of aHUS patients have preserved kidney function at initial presentation, and approximately 13% of aHUS patients may lack thrombocytopenia at initial presentation. Indeed, there seems to no ‘typical’ presentation among atypical HUS patients. Given the diverse symptoms and organ involvement, we present information that begins to build a compelling case for a multidisciplinary approach to aHUS disease diagnosis and management.

Thrombotic Microangiopathy Symposium- Through the Lens of aHUS

24 August 2017 in Boston (Click HERE FMI)

#TMAboston: pdf of AGENDA, TMA Symposium 24 August 2017

Specialty: Neurology (Brain & Central Nervous System)

“Central nerve system involvement is the most frequent extra-renal organ manifestation of aHUS (10–48%)” and “The largest aHUS cohorts describe cerebrovascular complications due to aHUS onset in 5/45 (11%; 1 CFH, 1 CFI, 3 without known mutation), 23/211 (11%; 5 CFH, 2 CFI, 1 C3, 1 CFH-Ab, 14 without known mutation), 6/45 (13%; 1 C3, 1 CFB, 1 CFH-Ab, 3 without known mutation), and 11/23 (48%; no genotyping) patients. “ Extra-Renal Manifestations of Complement-Mediated Thrombotic Microangiopathies (Hofer et al, 2014)

“…the first patient showed progressing thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) despite daily PE, and neurological manifestations (seizures, vision loss, loss of balance, and confusion) developed after 1 month. The second patient developed cerebral TMA (seizures, vision loss, and nystagmus) 6 days after initial presentation and remained unresponsive to PE/PI.” (Note: PE plasma exchange and PI fresh frozen plasma infusion) Neurologic involvement in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and successful treatment with eculizumab (Gulleroglu K et al, 2013)

“However, extrarenal manifestations are observed in approximately one-fifth of aHUS patients, with the myocardium and central nervous system (CNS) being involved most often. Additionally, there have been a few reports of aHUS with cerebral artery stenoses or periphereal gangrene, suggesting the possibility of ‘macrovascular’ involvement in aHUS.” Macrovascular involvement in a child with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (Ažukaitis, K et al, 2014)

“Common neurological complications in CKD include stroke, cognitive dysfunction, encephalopathy, peripheral and autonomic neuropathies.” and “While cognitive impairment is recognised as a common complication of CKD, it remains poorly identified. The reported prevalence of cognitive impairment in dialysis is estimated at between 30% and 60% while less than 5% of patients have clinically documented histories of cognitive impairment. Evidence suggests that both the prevalence and progression of cognitive impairment are inversely associated with the level of kidney function. Several large population-based studies have demonstrated an increased risk of cognitive decline in the presence of moderate CKD including an 11% increased prevalence of cognitive impairment per 10 mL/min/1.73 m2 decrease in eGFR.” Neurological complications in chronic kidney disease (Arnold R et al, 2016)).

See more: aHUS Alliance article Brain Fog and Kidney Disease?

Specialty: Cardiology (Heart, Cardiovascular)

“Cardiovascular complications have been reported in about 10% of aHUS patients including cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, myocarditis, and heart failure as well as steno-occlusive coronary lesions” and “Thus, especially patients with genetic or acquired CFH and C3 defects appear to be at highest risk for cardiac complications due to microangiopathic injury in the coronary microvasculature.” Extra-Renal Manifestations of Complement-Mediated Thrombotic Microangiopathies (Hofer et al, 2014)

Cardiac infarction related to a coronary thrombotic microangiopathy: “This is the first case of aHUS related to a mutation in the factor H gene associated with cardiac microangiopathy. This case emphasizes the need to screen for cardiac complication during the treatment of aHUS.” Myocardial infarction is a complication of factor H-associated atypical HUS (Sallée M et al)

“Cardiac complications occur in 3–10% of patients with complement-mediated aHUS, as a consequence of microangiopathic injury in the coronary microvasculature, and can cause sudden death. Emerging evidence also suggests that either thrombosis or stenosis of the medium and large arteries might complicate disease course, and such disorders occur even after renal function is lost. I “ Cardiovascular complications in atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome (Noris M and Remuzzi G, 2014) TABLE 1: Studies describing cardiovascular and macrovascular complications in aHUS.

Specialty: Dermatology (Skin)

“Skin involvement is a rare but maybe under diagnosed complication in the context of complement-mediated TMA and is reported for three patients in the literature.” and “The macroscopic picture of all three patients with the clear diagnosis of aHUS was similar and compatible with a cutaneous small-vessel vasculopathy potentially induced by a complement-mediated TMA. In addition, the skin histology of the only patient who underwent biopsy was compatible with TMA.” Extra-Renal Manifestations of Complement-Mediated Thrombotic Microangiopathies (Hofer et al, 2014)

“The skin biopsy has potential to play a very important role in the diagnosis of aHUS.” and “Two patients in our series had skin lesions in the context of symptomatic atypical HUS emphasizing that the skin is a targeted organ site despite the infrequency with which cutaneous involvement has been reported. There are only two prior reports of cutaneous lesions in the setting of atypical HUS. One child presented shortly after birth with thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia and acute renal failure. His course was complicated by multiple intestinal perforations and cutaneous ulcers.” The Role of the Skin Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. (Magro C et al, 2015)

“Skin involvement is not a commonly reported finding, but both clinically apparent and sub-clinical involvements have been described in some recent publications [6, 7]. We describe, herein, a unique case of aHUS highlighted by recurrent pancreatitis, ischemic colitis, and preserved renal function, with pathological assessment demonstrating microvascular thrombosis and endothelial complement deposition in colon and skin.” An Atypical Case of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: Predominant Gastrointestinal Involvement, Intact Renal Function, and C5b-9 Deposition in Colon and Skin (DeYao et al, 2015)

“Skin involvement in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is very uncommon and therefore often unrecognized as a specific symptom of aHUS. We describe 3 cases of patients with aHUS who developed skin lesions that completely recovered when disease-specific treatment was established. These cases suggest that in individuals with aHUS, when skin lesions of unknown origin occur, the possibility that they are due to thrombotic microangiopathy should be considered.” and “Two years later,while still on HD therapy, the patient was referred to our center because of persistent (10 months) lower-limb skin lesions characterized by numerous violaceous maculopapules that tended to coalesce centripetally, several petechiae, and ulcerative-necrotic lesions with well-defined borders, covered by eschar.” Skin Involvement in Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (Ardissino G et al, 2013)

Specialty: Pulmonary Medicine (Lungs)

“Pulmonary haemorrhage is a potentially life-threatening event that may occur in patients with pulmonary-renal syndromes. These syndromes have typically been thought to occur in small-vessel vasculitides, such as ANCA-mediated disease, Goodpasture’s disease and other autoimmune conditions including systemic lupus erythematosus or anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome. Here, we present a rare cause for pulmonary haemorrhage with associated renal failure—atypical haemolytic-uraemic syndrome. In this case, renal biopsy was integral to providing a diagnosis and guiding therapy.” A rare cause of the pulmonary-renal syndrome: a case of atypical haemolytic-uraemic syndrome complicated by pulmonary haemorrhage Derebail V et al, 2008)

“Atypical HUS is not a commonly recognized cause of pulmonary-renal syndrome because DAH has only rarely been reported as a complication of aHUS. Patients diagnosed with aHUS should be closely monitored for progressive hypoxia and DAH. Not Your Typical Pulmonary – Renal Syndrome: Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Complicated By Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage (Kaur A et al, 2014)

“ Significant physicial examination findings were rhonchi with decreased breath sounds at the bases. She was intubated for respiratory failure and blood-tinged secretions were noted in the endotracheal tube.” Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage in a Patient With Atypical Hemolytic Uremia Syndrome (Zahiruddin F and Zimmerman J, 2016)

“Clinically, significant pulmonary TMA manifestations are only anecdotally reported in the literature and mainly in the context of multiorgan manifestations of severe and fulminant complement-mediated TMA. Approximately 5% of patients with aHUS present with a life-threatening multivisceral failure due to diffuse TMA including cardiac ischemic events, CNS complications, pancreatitis, intestinal bleeding, hepatic cytolysis, rhabdomyolysis, and pulmonary hemorrhage and failure.” Extra-Renal Manifestations of Complement-Mediated Thrombotic Microangiopathies (Hofer et al, 2014)

Specialty: Gastroenterology (Digestive tract, Pancreas, Liver)

“Pancreatitis, intestinal bleeding and hepatic cytolysis are reported mainly in patients with life-threatening multivisceral failure due to diffuse TMA (5% of patients with aHUS.” and “A number of reports describe intestinal TMA in the context of post-solid-organ transplant TMA possibly triggered/caused by the use of calcineurin inhibitors (Cyclosporin A, Tacrolimus). Intestinal TMA was diagnosed histologically. Patients presented with abdominal colics, constipation, abdominal distension, strictures, occlusions, and even intestinal perforations.” Also, “Pancreas involvement in patients with HUS or TTP is reported frequently. Pancreatic ischemia caused by HUS/TTP may contribute to the common symptom of abdominal pain.” Extra-Renal Manifestations of Complement-Mediated Thrombotic Microangiopathies (Hofer et al, 2014)

“Despite those reports, Ohanian et al report on severe neurological and intestinal involvement in a patient with complement activation on the basis of aHUS responsive to eculizumab (genotyping is not reported). The 50-year-old female presented with diarrhea and abdominal pain subsequently developing fulminant pancolitis with acute renal failure and thrombocytopenia.” Extra-Renal Manifestations of Complement-Mediated Thrombotic Microangiopathies (Hofer et al, 2014) Referenced: Eculizumab safely reverses neurologic impairment and eliminates need for dialysis in severe atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. (Ohanian M et al, 2011) and Reduced dose maintenance eculizumab in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS): an update on a previous case report. (Ohanian M et al, 2011)

“Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) in allograft kidney transplantation is caused by various factors including rejection, infection, and immunosuppressive drugs. We present a case of a 32 year old woman with aHUS four years after an ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation from a living relative. The primary cause of end-stage renal disease was unknown; however, IgA nephropathy (IgAN) was suspected from her clinical course. She underwent pre-emptive kidney transplantation from her 60 year old mother. The allograft preserved good renal function [serum creatinine (sCr) level 110–130 μmol/L] until a sudden attack of abdominal pain four years after transplant, with acute renal failure (sCr level, 385.3 μmol/L), decreasing platelet count, and hemolytic anemia with schizocytes. On allograft biopsy, there was thrombotic microangiopathy in the glomeruli, with a cellular crescent formation and mesangial IgA and C3 deposition. Microvascular inflammation, such as glomerulitis, peritubular capillaritis, and arteriole endarteritis were also detected.” Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome diagnosed four years after ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation (Kawaguchi K et al, 2015)

“Case Report: A 62-year-old Filipino man with a history of chronic kidney disease stage 3 and diabetes mellitus type 2 experienced a decline in renal function with abdominal pain, arthritis, and palpable purpura a year prior to diagnosis of aHUS. Renal biopsy at the time revealed, on immunofluorescence microscopy, mesangial IgA deposits consistent with IgA vasculitis.” Diagnosis of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome and Response to Eculizumab Therapy (Nguyen M et al, 2014)

“We describe, herein, a unique case of aHUS highlighted by recurrent pancreatitis, ischemic colitis, and preserved renal function, with pathological assessment demonstrating microvascular thrombosis and endothelial complement deposition in colon and skin.” An Atypical Case of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: Predominant Gastrointestinal Involvement, Intact Renal Function, and C5b-9 Deposition in Colon and Skin (DeYao et al, 2015)

Specialty: Ophthalmology (Eyes, Vision)

“Ophthalmologic examination found vitreous bleeding, elevated ocular pressure, choroidal hemorrhage (ultrasound biomicroscopy) and retinal ischemia (fluorescein angiography).” Ocular involvement in hemolytic uremic syndrome due to factor H deficiency–are there therapeutic consequences? (Larakeb A et al, 2007)

“This report describes a patient with aHUS with bilateral central retinal artery and vein occlusion, vitreous hemorrhage, and blindness in addition to renal impairment .” and “After reporting vision loss during which she was only able to see light and faint color, significant bilateral retinal damage including disc, macular, and retinal hemorrhages in all four quadrants to the mid-periphery was identified and presumed irreversible.” Case report of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome with retinal arterial and venous occlusion treated with eculizumab. (Greenwood, G 2015)

“Research linked aHUS to genetic abnormalities in the complement system proteins like: factor H, factor I, membrane co-factor protein, factor CD46, factor B, and C3. Ocular manifestations are rare and include retinal, choroidal, and vitreal hemorrhages, retinal ischemic signs, and non-perfusion.” Resolution of ocular involvement with systemic eculizumab therapy in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. (David R et al, 2013)

Atypical HUS patients and caregivers of pediatric aHUS patients mentioned vision issues as an area of concern for them in the 2016 aHUS Global Poll (see questions 39 and 40). This aHUS Alliance poll involved 233 participants from 23 nations answering 45 questions on a survey tool made available in 6 languages. Of the adult aHUS patients and caregivers of pediatric patients, 50 of 233 respondents noted that vision issues were a serious or frequent enough concern for them to mention vision issues to their doctor (Q 39).

See more: aHUS Alliance article Vision Issues & aHUS

Specialty : OB–GYN (Pregnancy and Postpartum)

“When a pregnant or postpartum woman develops severe microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) and thrombocytopenia, three syndromes must be considered: (1) preeclampsia with severe features/hemolysis, elevated liver function tests, low platelets (PE/HELLP) syndrome; (2) thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP); and (3) complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy (C-TMA; also referred to as atypical hemolytic–uremic syndrome).” Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy associated with pregnancy (George J, Nester C, and McIntosh J, 2015)

“P-aHUS (pregnancy-associated aHUS) occurred in 21 of the 100 adult female patients with atypical HUS, with 79% presenting postpartum. We detected complement abnormalities in 18 of the 21 patients.” and “Our data clearly underline that pregnancy is definitely an important triggering factor for aHUS. Moreover, the outcome is severe, with more than two-thirds of patients reaching ESRD, mostly in the month after the onset. P-aHUS shares with non-pregnancy-related aHUS a high incidence of mutations in complement genes (86% and 76%, respectively), with CFH mutations being the most frequently encountered (48% of patients).” Pregnancy-Associated Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Revisited in the Era of Complement Gene Mutations. (Fakhouri F and Roumenina L et al, 2010)

From the aHUS Alliance Article on Pregnancy & aHUS: High blood pressure (hypertension) during pregnancy affects 6% to 8% of pregnant women. Pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH) can occur at various stages of pregnancy, have many causal factors, and can vary greatly in severity and duration. High blood pressure may develop after 20 weeks of pregnancy but resolve on its own after birth (gestational hypertension). Pre-eclampsia is a complication that generally occurs in the last trimester of pregnancy, affecting about 1 in 20 pregnancies. Symptoms of pre-eclampsia include a sudden and sharp rise in blood pressure, swelling (edema) in the face hands, and feet, and excess protein in the urine (albuminuria). A serious condition that can affect both mother and child, pre-eclampsia can occur during pregnancy or after delivery (postpartum), and having it once increases the risk that pre-eclampsia may affect future pregnancies as well. Of those women who develop pre-eclampsia, an estimated 15% can be affected by HELLP syndrome, a serious liver and blood clotting disorder marked by red blood cell destruction or Hemolysis (H), Elevated Liver enzymes (EL) and Low Platelet count or thrombocytopenia (LP). With red blood cell destruction, impaired blood clotting ability, and liver function issues, HELLP can threaten the mother’s life and potentially cause lifelong health problems. Sorting out these issues is difficult, even for medical personnel familiar with aHUS diagnosis and treatment.

See more: aHUS Alliance article Atypical HUS & Pregnancy

Additional Information

Visit our aHUS Info Center

for updated RESEARCH and new RESOURCES

Detailed Medical Overview of Atypical HUS

Genetic Atypical Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome (Noris M et al, 2016)

Multi-Organ Involvement

Extra-Renal Manifestations of Complement-Mediated Thrombotic Microangiopathies (Hofer et al, 2014)

aHUS in the ICU: Multi-Organ Involvement

Expert Statements on the Standard of Care in Critically Ill Adult Patients With Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (Azoulay E et al, 2017)

Slide from a presentation by Dr. Carla M Nester, U of Iowa (aHUS Conference 2013) Video Clip: www.bit.ly/2GYiy1j

aHUS Alliance

Info Centre: Documents

Atypical HUS Clinical Channel – YouTube

Contact Us: info@aHUSallianceAction.org

Twitter: @aHUSallianceAct

May 2017, L Burke

NEW Info & RESEARCH

The aHUS Alliance strives to keep information updated, below find TMA research and information available after this article was published online. Contact us if you have suggestions to add to this, or other aHUS Alliance articles E: info@aHUSallianceAction.org

Aug 2018: Article

Extra-renal manifestations of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Formeck, C. & Swiatecka-Urban, A. Pediatr Nephrol (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-018-4039-7

Thrombotic Microangiopathy: A Multidisciplinary Team Approach

Craig E. Gordon, Vipul C. Chitalia, J. Mark Sloan, David J. Salant, David L. Coleman, Karen Quillen, Katya Ravid, Jean M. Francis.

American Journal of Kidney Diseases

http://www.ajkd.org/article/S0

This research triggered a partnership in physician education. Lead author Dr Craig Gordon, and contributing author Dr Jean Francis, were among the Boston area physicians collaborating with for the August 2017 event Thrombotic Microangiopathy Sympsoium: Through the Lens of aHUS.

9 presentations from TMA Boston, all including the aHUS Patient Voice from 3 nations (Canada, UK, USA) describing their patient experiences with atypical HUS diagnosis, quality of life & personal impact, and impact of aHUS on multiple organs.

Watch the Videos, click HERE for the TMA Boston video playlist: Thrombotic Microangiopathy Sympsoium: Through the Lens of aHUS (Atypical HUS Clinical Channel of the aHUS Alliance)

Article about TMA Boston: Click HERE to read the aHUS Alliance article.

Clinical Tracker Tool, pdf download

![]()