Dr Errol Gottlich and Professor Mignon McCulloch

Resilience, fortitude and determination.

These characteristics describe the South African doctor treating patients within a complex and changing health system. Atypical HUS, with its diagnosis and disease complexity, specialist management and various treatment modalities pushes these characteristics to the limit for doctors worldwide, and especially in lower and middle income (LMIC) countries.

HUS is a well-known condition to doctors in South Africa since many early papers on the subject were published by South African paediatricians.¹ ² ³

With the later recognition of aHUS as a syndrome, the challenges that this condition raised became immediately apparent. Worldwide, the issues of syndrome recognition, early referral, plasma exchange and ongoing morbidity and mortality due to haemolytic activity became very apparent and problematic.

The advent of molecular testing, including serial single-gene testing, the multi-gene panel, comprehensive genomic testing as well as complement antibody recognition made the assessment of a child with aHUS far more scientific and treatment focused.

Eculizumab, originally registered for paroxysmal nocturnal haematuria and later for aHUS, was a ground-breaking therapy to expand treatment options for aHUS. Alexion Pharmaceuticals developed eculizumab and remain the sole distributor based on strict clinical entry criteria which their medical team manages. Eculizumab came however, especially to LMIC countries, at an unaffordable price and with very restricted access, if any at all! This is in stark contrast to countries like the UK where the NHS funds this drug for aHUS.

South African health services, a tale of two cities.

The South African health service has two parallel streams. Approximately 45 million people rely on a public health system which is financially restrained and will not support the enormous financial costs that eculizumab incurs. Patients in the public sector cannot therefore access this therapy unless they are eligible for a global assistance program. Alexion Pharmaceuticals, however, has made it clear that their global assistance program is not as global as the name suggests and will not include many LMIC countries. South Africa`s other 9 million citizens are privately insured and have variable access to eculizumab depending on the pressure the patients and the doctors exert on the health funder. The funder is under no legal obligation to support a drug that is not registered in this country and therefore funding is only achieved through significant motivation and is entirely dependent on the ability of the individual funder to afford the therapy within a large insurance risk pool. Although some funders understand the rationale to support rare diseases with high cost therapies they impose an ongoing co-payment requirement on the family, which in itself is unaffordable and unsustainable. The reality therefore is that long term eculizumab therapy remains elusive to both private and public patients in South Africa.

Local challenges in the management of aHUS

In South Africa we have been faced with the challenge of diagnosing and treating a number of children with aHUS over the last few years. We rely on international laboratories (USA or UK) to make the diagnosis, which in itself presents the problems of affordability due to our weak currency, the transport of blood products across international borders as well as the delay in getting results. Recently, an Indian laboratory is able to offer some of the aHUS testing at a lower price.

The acute management of aHUS depends on urgent administration of appropriate therapy which may include eculizumab. This urgency is impeded by a prolonged diagnostic time due to overseas testing. Further delay in our cases has been due to prolonged and difficult communication with Alexion Pharmaceuticals. Importing eculizumab, when it has become possible, relies on permission being granted by the Medical Control Council. Together all these factors inevitably deny new patients urgent access to eculizumab in the important acute phase of the disease presentation thus significantly increasing the risk of irreversible renal failure and even worse mortality.

Trying to obtain access to eculizumab from Alexion Pharmaceuticals has been extremely problematic from an ethical and professional perspective. In doing so we have been supported by leading international specialists in the field and the aHUS Alliance global action group. This support shown to us, our patients and the families has been overwhelming. One would think that the introduction of such a profoundly important therapeutic agent would be primarily motivated to ensure that patients with this rare and severe disease have access to the drug. Surely that’s what we in medicine consider. Sadly that is not what Alexion Pharmaceutical`s primary focus seems to be. Alexion Pharmaceutical has made eculizumab exclusively available for the higher income countries in the western world at a price that has elevated it to an unfortunate title as one of the world’s most expensive drugs. South Africa has a recent and painful experience of racial, social and financial discrimination. Being exposed to medical discrimination only adds to an unjust international action on a specific part of the world that is very sensitized to human rights issues.

Patient experience

At the time of our 1st patient, eculizumab was not registered for aHUS. Alexion Pharmaceuticals refused, after months of acrimonious discussions, any access to the drug for our patient – even just to cover the peri-operative period. We therefore went ahead and thankfully achieved a successful outcome with a combined liver and kidney transplant for that patient under plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy.

Our 2nd patient was highly pre-sensitized due to a previous kidney transplant and was on the waiting list for a prolonged time. After significant international pressure was exerted on Alexion Pharmaceuticals, 2 weekly eculizumab therapy was provided at no cost until he too had a successful combined liver and kidney transplant under eculizumab cover. We were grateful to Alexion Pharmaceuticals in making the therapy available pro deo for a limited period although it only happened after unrelenting pressure including assistance from the aHUS Alliance global action advocates. The choice of combined liver and kidney transplants for both patients was made as there was no possibility of a kidney transplant alone as lifelong eculizumab was not accessible nor affordable.

Thankfully, by the time our 3rd patient, a 4 month old little girl, presented with aHUS pre-renal failure, we were able to acutely administer eculizumab that was still available after our 2nd patient. This, no doubt, prevented her progressing into renal failure. Alexion Pharmaceuticals instructed us to destroy any other vials that we had but we were fortunate in purchasing further vials which we have used only once when she became active again a number of months after her first presentation. Fortunately it has not been clinically necessary to keep her on continuous preventative therapy with eculizumab.

Even more recently we have had a further patient who had funding to do the testing and was positive for aHUS but unfortunately the patient had other medical complications which contra-indicated a combined liver kidney transplant. Long term eculizumab therapy was not a financial option, resulting in the death of this patient.

Sadly a number of other children with aHUS within the public sector have not survived the illness due to significant medical complications compounded by very poor socio-economic circumstances. Others have also had suspected aHUS (at least 3 patients in Cape Town) but there was no funding to do the testing and so too these children died.

One can therefore appreciate the extreme anxiety that parents and doctors go through when faced with a child who has a life threatening condition such as aHUS. In the best of circumstances, this condition requires extensive commitment and support but for those in LMIC, the added stress of trying to access a restricted and unaffordable therapy severely erodes one’s commitment to provide the best of care.

A new way ahead.

There is a need for a new model of access to eculizumab and other new complement blocking agents for aHUS. This is a model that can be equally used for other similar circumstances where expensive drugs exist for rare severe conditions. It is an inclusionary model that morally and ethically recognizes that all children with aHUS, wherever they are, can have at least have a fair opportunity to access treatment.

It is vitally important that Pharma realize that it cannot be business as usual. Worldwide, corporate values are being directed towards “doing good”. To achieve that we would like to suggest a new model for making complement blocking agents available to patients in the LMIC countries where funding of the therapy is not available. Pharma, doctors and patients should collaborate positively. There is an urgent need to create a joint partnership. The profession needs to manage clinical adjudication. Pharma needs to control supply, storage and distribution. Patients need to be supported by their attending specialists as well as civil society, in this case the aHUS Alliance global action advocates

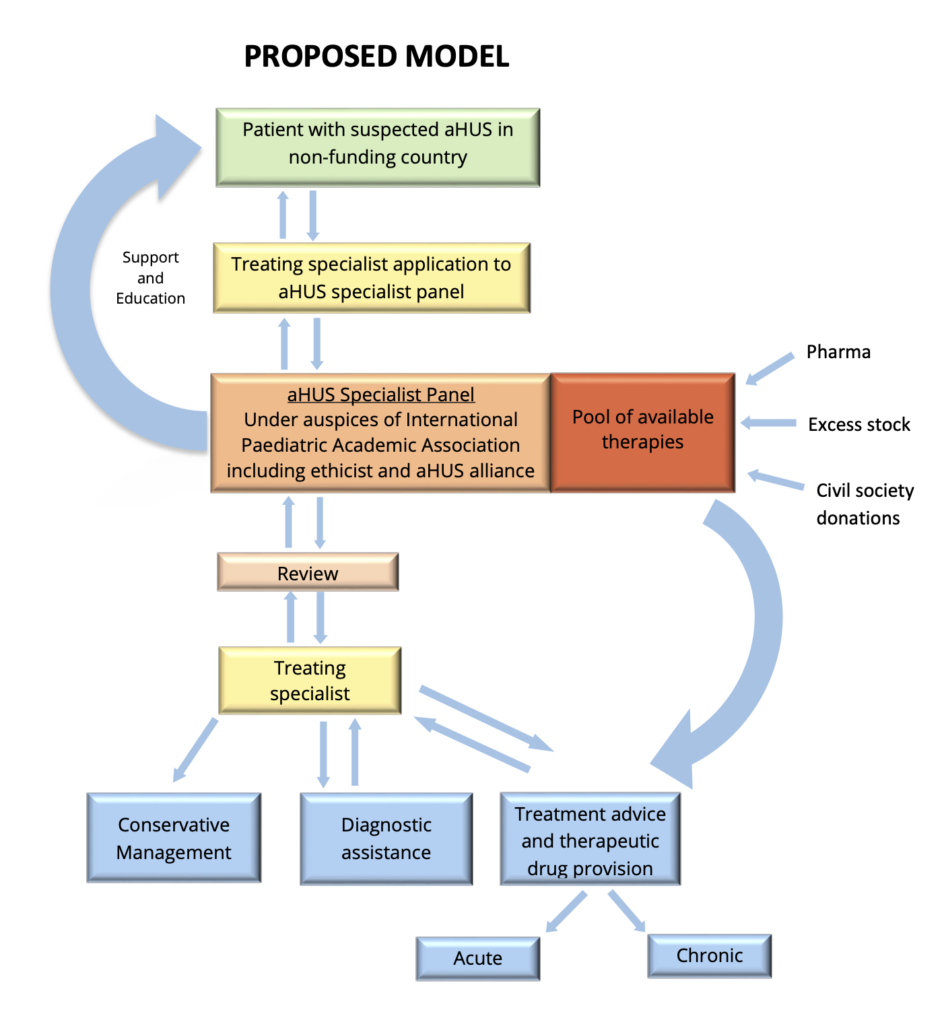

This model for access to complement inhibitors for aHUS is depicted in Figure 1. It suggests the formation of an advisory panel made up of experts in the field, an ethicist and representation from civil society including members and parents of the aHUS Alliance. The panel needs to be supported and constituted under the umbrella of an international paediatric representative organization such as the International Paediatric Nephrology Association (IPNA) or HUS International (HUSi).

The panel needs to have immediate access to a pool of donated funds and drug stock. Drug stock should be donated by the pharmaceutical companies under their corporate social responsibility program. Excess stock, when not used, should also be channeled to the pool of therapy. Additional funds to purchase therapy can be sourced from donors. The drug stock pool will be stored by the pharmaceutical company and distribution will be instituted on the instruction of the panel.

After recognition of a child with possible aHUS in LMIC countries, an urgent application is made by the treating specialist to the panel to review the case from both a clinical and socio-economic perspective.

The panel will then guide the referring specialist in further management whether it be:

- Diagnostic with cheaper testing now available in regions such as India

- Conservative with a palliative care approach to management or

- Therapeutic which may include eculizumab.

If the panel feels that the child warrants urgent therapy then therapy should be made available from the available drug stock pool for a limited period of time. The treating specialist should be assisted, logistically and financially, to ensure a comprehensive diagnosis. The panel should then, together with the treating specialist, formulate the best and most appropriate treatment plan possible based on financial, social, medical and ethical circumstances. This may or may not include therapies such as plasma exchange, complement blocking agents and transplantation due to variable circumstances that may apply. The panel will continue to support the referring specialist in the treatment journey. A comprehensive registry of treatment requests and outcomes needs to be a responsibility of the panel.

We believe the above co-operative approach will change the current impasse that exists and will create a far more just and equitable environment for all involved in the management of this complex condition.

We have written this perspective from a South African point of view, but following extensive training of paediatric kidney experts throughout Africa, there are increasing cases being identified in other parts of Africa who would also benefit from the above proposal. Specialists treating aHUS patients in other nations face similar treatment restrictions and issues of policy or economics, amplifying the need for a new global access model.

In Africa we have an ancient and wise saying that says,” It takes a village to raise a child”. In the context of the value of a child’s life with aHUS it has become necessary to extend that saying to “it takes a global village to raise a child”.

We would like to thank all those who care. Our colleagues, the aHUS Alliance, parents, family members and members of society who continue to work tirelessly to ensure that children, wherever they are, face a devastating diagnosis with hope.

Authors

- Dr Errol Gottlich is a Paediatric Nephrologist in private practice at Morningside Mediclinic and the University of Witwatersrand Donald Gordon Medical Centre in Johannesburg and an Honorary Lecturer at the University of Pretoria. He is also the clinical manager of the KidneyCare program at Discovery Health.

- Professor Mignon McCulloch, Consultant Nephrologist/PICU at Red Cross Children’s Hospital, University of Cape Town, also current President of African Paediatric Nephrology Association, Committee member of HUSi.

Correspondence

Dr E Gottlich, errolg@discovery.co.za

References

- Kaplan BS, Drummond KN. The hemolytic-uremic syndrome is a syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1978; 298:964-966 [PubMed)

- Kaplan BS, Meyers KE, Schulman SL. The pathogenesis and treatment of hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998; 9:1126-1133 [PubMed]

- Barnard PJ, Kibel M. The haemolytic-uraemic syndrome of infancy and childhood. A report of eleven cases. Cent Afr J Med. 1965; 11:31-34 [PubMed]