Article No. 425

30 March 2021

Dealing with the rare disease atypical HUS is difficult, for both patients and for those involved with their care. It’s difficult for parents to watch their child go through a rare and life-threatening disease like aHUS. Imagine what it’s like to be an adult in the throes of aHUS activity, missing work and perhaps dealing complex care issues due to seizures, kidney failure or damage to vital organs such as the heart.

Spouses or partners may want to be at hospital bedside with their loved one but feel torn among different roles and juggling everyday responsibilities. How do viewpoints and experiences differ for pediatric caregivers versus adults navigating their own aHUS care and its impact? Does involvement of a family caregiver have a positive impact on certain aspects of living with the disease, help in receiving a more rapid and accurate diagnosis, reduction of ‘disease burdens’ or expansion of available aHUS treatment options?

Can ‘experiencing aHUS’ mean quite different things to people depending on their lifestyle, role, and support system – and if so, how? There’s no one definition on wellness, though predictably there is consensus that people with aHUS want to be active participants in all that life can offer in terms of lifestyle, work/life balance, and the strength drawn from supportive, caring relationships. An interesting area that’s often neglected is the relationship with, and viewpoints of medical professionals so we include that as an important aspect to consider.

Common Views & Concerns

There are a group of common questions that often arise no matter the nationality of the patient or family caregiver, and which were detailed in the aHUS Patient Research Agenda. As one might expect, diagnosis and treatment issues anchor many concerns but the impact of atypical HUS affects all areas of life for patients and their families. Questions within a family often change over time: as teens transition to adult care, when thinking about transplants or discontinuing a drug, or when wondering about circumstances which might have triggered an initial aHUS episode moves forward into worries about aHUS relapse risks.

Those experiencing extensive kidney damage that leads to organ failure and dialysis may worry about mounting comorbidities while they await a kidney transplant (which may be years distant). Young couples wishing to start a family may have concerns about pregnancy as a trigger for aHUS activity as well as concerns about inherited genetics, or perhaps potential guilt about passing along a genetic predisposition to this rare disease. Mounting medical bills and lost time at work or school may affect both economic security and mental health, with ripples of stress which can be felt throughout by family members regardless of their age or roles.

Finding and sharing information, weighing treatment options, coordinating care and appointments, and similar issues aren’t just problematic within the realm of the atypical HUS community but are common to many families facing rare disease care. One recent study (Simpson et al, 2021) “identified two key consequences of uncoordinated care on the patient and carer experience—delays and barriers in accessing care and additional time/burden. A range of impacts on patients and parents/carers were identified and grouped into three overarching themes relating to physical health, psychosocial impacts and financial impacts.” Family changes, social support, financial burdens, and personal experiences vary widely depending on caregiver relationships and roles.

When your Child has aHUS – the Parent Experience

When a child has any serious illness, friends and family members often join with parents in expressing concern and a desire to provide support. People with atypical HUS may experience delayed diagnosis due to the complex nature of the disease, differences in how the disease presents and vagueness of symptoms, variety of damage to organs other than kidneys, and confusion about lack of a specific test to clearly identify aHUS apart from other syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy.

What makes it additionally difficult for parents caring for a child with a rare disease is dealing with social/developmental needs as well as medical care, all framed by a sense of isolation and lack of information. Mothers and fathers in Italy who are caregivers for their children with a rare disease participated in a study that found, “Parents, in particular, discussed feeling anxious about being the ‘expert’ and being responsible for looking out for symptom changes and receiving little support. Isolation was also a common theme amongst parents…” (Cardinali et al, 2019). In their 2019 article for Child: Care, Health and Development, Currie and Szabo noted in their research results: “Four insights were also revealed: (a) Parents often know more about the disease then Health Care providers, and this leads to entanglements in communication and collaboration as experts and parents; (b) there is lack of coordination of care between providers and services caring for children with rare diseases; (c) there is a gap in accessibility to government supports; and (d) due to fragmented care, parents must fill the aforementioned gaps by juggling multiple roles including that of advocate, case manager, and medical navigator.”

All parents wear many hats while going through daily life full of its normal demands and juggling home and work responsibilities. Often this is compounded by guilt when parents feel they are neglecting other children in their household. Parents caring for a child with aHUS face additional demands of increased stresses and time crunch due to: at-home medical routines, specialist appointments, infusions and blood draws, navigating insurance, and finding coverage for tasks at work or home. Guilt and worry can result in parents experiencing an unhealthy dose of self-blame mental messages that begin with “If only”. That seems especially true with regard to family and the siblings of children with a rare disease, as they too must cope with its emotional impact and consequences on family life. (See UK report, understanding children & sibling experiences).

When an Adult has aHUS – and the Experience of those in Support/Caregiving Roles

If you’re an adult living with atypical HUS your wellness may last for decades, but also you’re aware that aHUS relapses can occur without warning. You’re able (and perhaps willing) to participate in online support groups, keep abreast of aHUS research, participate in rare disease events such as aHUS Awareness Day, and maybe even advocate within your nation for healthcare issues that directly affect you and your family. Yet many adults who have experienced wellness after atypical HUS simply need a respite period to regain balance in their lives and to put back together the pieces of their life that illness has torn apart or simply worn down. After having run the marathon of visits to clinics and specialists regarding aHUS treatment, it’s understandable that adults diagnosed with aHUS wish to recapture a sense of normalcy and enjoyment in their activities, roles, and relationships.

In some cases there’s a slow progression toward illness, while other patients seem to have ongoing issues with low level or ‘smouldering’ aHUS activity. Since aHUS symptoms are often vague or not overt, it can trigger misperceptions common to other medical conditions considered to be “invisible illnesses”. For those experiencing aHUS acitivty, severity of symptoms and organs impacted can vary widely (see Azoulay et al, 2017) with some needing intensive care. Adult aHUS patients may need to rely on their ‘circle of support’ to provide assistance, assume or delegate responsibilities at home or work, help navigate healthcare and coordinate appointments, discover patient education and assistance options, weigh treatment options, check into clinical trials and research advancements, and assume caregiving or support functions. A spouse or partner can fill these roles, but adult children or siblings may also step in to assist.

While family caregivers can find support groups and helpful materials, spousal caregivers will find few resources. Financial stress may be an issue, along with shouldering an extra share of responsibilities at home, but loss of spousal companionship and intimacy are aspects seldom addressed. Mental and emotional health for both adult patients and for their caregivers are often neglected in the flurry of urgent medical needs.And for some adult patients and caregivers there may be a loss of identity as lifestyles change, presenting at times a complex relationship between rare diseases and mental health issues (R Nunn, 2017) such as depression or anxiety.

When your Patient has aHUS – the Physician Experience

An area not often mentioned are viewpoints of medical professionals who encounter patients whose symptoms and test results fall outside common clinical experiences. From a PharmaLive interview with Dr Daniel Zaksas, “Physicians are also now being asked to understand, diagnose, and treat many more diseases, including diseases that they might have heard mentioned once at a lecture in medical school. So, that’s a challenge.” further noting, “The education part is not the challenge – the challenge is the motivation. Physicians have a great capacity and desire to learn new information. However, the material they choose to stay on top of must be that which is the most relevant to their practice. When you ask them to retain new information about the diagnosis of a rare disease, you have to communicate very clearly why retaining that information will make a real difference to the well-being of their patient. Ironically, what often motivates physicians to look for a rare disease is the knowledge that an effective therapy is either approved or in development for that disease.”. But what’s likely to happen when healthcare providers encounter a new patient with an unusual presentation, and need to reach beyond their experiences to explore the rare disease realm of over 7,000 conditions?

According to an article regarding medical care for rare diseases (JK Stoller, 2018), “Characteristically, in rare diseases, knowledge and experience with managing such diseases are concentrated in those (usually relatively few) dispersed centers where clinicians have taken special interest and have developed deep experience with these conditions. Understandably, a clinician’s expertise in managing a disease is proportional to the frequency with which he/she encounters and manages patients with the disease.” However the patients’ initial presentation with aHUS most often would be outside such centers of expertise, with the more likely route of an appointment with their local general practitioner or primary care physician. What’s the perspective of healthcare professionals on diagnosing and treating patients with a rare disease? How do medical students feel about rare disease knowledge and preparedness during their education and training? (i.e. Poland, Domaradzki & Walkowiak 2019)

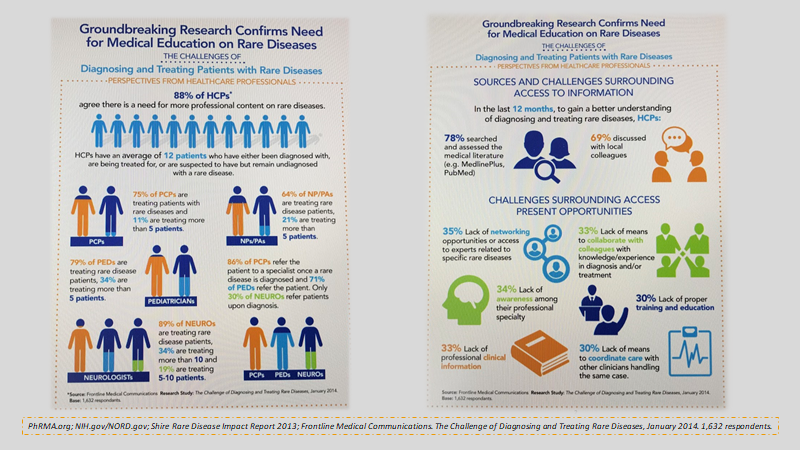

A variety of sources underscore the need for both more information about rare disease at medical schools and in training, with continuing education opportunities for medical professionals. A few facts from an interesting series of infographics by Frontline Medical which were based on 2014 research study: The Challenge of Diagnosing and Treating Rare Diseases (infographics pdf). Need seems overwhelming, according to this source, as 88% of Health Care Professionals (HCPs) noted the need for more professional content on rare diseases, as they saw an average of 12 patients diagnosed with, treated for, or are suspected to have a rare disease.

This same series of infographics noted action steps from the 1,632 respondents involved in this 2014 study. Within the 12 months prior to the study, 78% of HCPs reported searched and assessed the medical literature (e.g. MedlinePlus,PubMed) and 69% had discussion with local colleagues to gain a better understanding of diagnosing and treating rare diseases. But differing experiences were reported by medical professionals. 79% of pediatricians (PEDs) noted treating rare disease patients, with 34% treating more than 5 patients. This same source reported that 86% of primary care physicians (PCPs) refer the patient to a specialist once a rare disease is diagnosed and 71% of PEDs refer the patient. Since atypical HUS activity can ramp up quickly, sometimes with catastrophic events, how does physician knowledge about rare disease diagnosis and treatment impact aHUS patient outcomes?

Click HERE to view the Frontline Medical Infographics (pdf)

With a disease as complex as atypical HUS, there remain many questions regarding how to navigate diagnosis and management of such a very rare condition. The patient experience is quite variable among many different subtypes and aHUS presentations: chronic aHUS, episodic aHUS, temporary damage but recovered kidney function, ESKD and dialysis, transplant types, slow or late-life onset, multi-organ involvement, and more. Experiences and outcomes vary for patients with access to aHUS complement inhibitors and for the majority of the world’s aHUS patients, who remain without drug access and thus limit physicians in low resource nations to plasma therapies. Information flow is fragmented in the aHUS space, which remains an issue for physicians and patients alike and was noted in our 2016 aHUS global poll results and continues to be problematic for aHUS clinical trials. Examining the patient journey of aHUS diagnosis is a central focus of the poll we conducted in the first quarter of 2021, with a report to be issues later this year, may serve to ‘connect the dots’ of patient diagnosis within the aHUS global community.