CardioRenal Syndrome:

There’s an interrelationship between Heart & Kidney Function

Cardiorenal syndrome is a fairly recent term to describe the long-recognized group of medical characteristics (syndrome) which coexist between heart (cardio) and kidney function (renal). When either the kidneys or heart are not fulfilling their vital tasks, there can be a harmful and two-way interaction where decline in one of these major organs can seriously undermine function of the other.

“Hence, it’s not just the heart whose decline could drag the kidneys down with it. In fact, kidney disease, both acute (short duration, sudden onset) or chronic (long-standing, slow onset chronic disease) could also cause problems with the heart’s function. Finally, an independent secondary entity (like diabetes) could hurt both the kidneys and the heart, leading to a problem with both organ’s functioning. Cardiorenal syndrome may start off in acute scenarios where a sudden worsening of the heart (for instance, a heart attack which leads to acute congestive heart failure) hurts the kidneys. However, that might not always be the case since long-standing chronic congestive heart failure (CHF) can also lead to a slow yet progressive decline in kidney function. Similarly, patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are at higher risk for heart disease.” (Thind GS et al. 2018)

FMI on roles of the kidneys and heart:

see Renal function World Kidney Day and Blood Pressure and Strokes, Heart.org

Given the complex relationship between kidney function and heart health, people with diseases that affect the kidneys or heart need to be aware that their medical treatment should include monitoring for both major organs. Kidney doctors (nephrologists) and heart specialists (cardiologists) are well aware that issues with blood pressure (hypertension) may cause dysfunction in both the heart and kidneys but are patients aware of the complex relationship between these organs?

People with chronic kidney diseases are often not informed that they should be contacting their physicians when they have symptoms which may be related to heart issues. The same holds true for patient education efforts to assist those with heart disease, in terms of information about the cardiorenal syndrome and the potential impact for kidney issues to arise. Are clinicians providing patient education about cardiorenal syndrome, and clearly indicating that patients need to contact their medical providers when experiencing symptoms indicating a decline in kidney function or warnings about heart attack or stroke? When people learn they have high blood pressure (hypertension), is the relationship between kidney and heart health emphasized in patient education efforts? For kidney patients who dialyze, does information provided to patients address this inter-relationship regarding fluid management, high blood pressure, and heart health?

We’ve conducted a brief review of the medical literature regarding cardiorenal syndrome. As an umbrella group for atypical HUS patient advocacy in over 30 nations, the aHUS Alliance presents research to launch discussions about complex inter-relationship between kidney disease and heart health. Links in the 3 “Research by Topic” sections below direct readers to medical articles and resources which focus on cardiorenal syndrome, with an emphasis on topics of dialysis and other areas of high interest to those interested in the ultra rare disease atypical HUS. (These three sections of research excerpts follow a brief overview of cardiorenal syndrome as it relates to the rare disease atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, or aHUS.)

An Overview:

Atypical HUS & Cardiorenal Syndrome

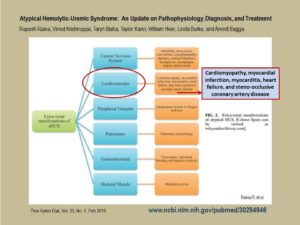

People with rare diseases like atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (atypical HUS or aHUS) may realize that part of their condition’s name (uremic) pertains to kidney function, issues but have little knowledge its potential to impact the heart. Although research varies, according to one aHUS patient education source (Alexion Pharmaceuticals, 2016), cardiac problems occur in an estimated “43% experience cardiovascular symptoms, such as heart attack and high blood pressure”. Data from Table 1 of Patient Demographics in the Global aHUS Registry (Licht et al, 2015) lists these heart issues as causes of death: cardiomyopathy, malignant cardiac arrhythmias, protracted cardiogenic shock and ventricular tachycardia.

Little wonder that among 24 key research questions posed by to the aHUS registry’s SAB by aHUS patient advocates the following year was “What is the incidence of (multi-organ) co-morbidities with aHUS for adults and children?” (Woodward L et al, 2016, see also the global aHUS Patients’ Research Agenda, 2019) Cardiac issues continue to be reported across the aHUS literature in summative reports on atypical HUS which mention extra-renal involvement, to include: cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, myocarditis, heart failure, and steno-occlusive, and coronary artery disease. (Raina et al, 2019) How well informed are aHUS patients and their family caregivers regarding the impact that atypical HUS may have on organs other than the kidneys (extra-renal manifestations)?

Information about cardiorenal syndrome may be found in hematology, nephrology, cardiology and other journals but research can also be found by utilizing a variety of key terms such as thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and complement disease. (Article & links on differentiating aHUS among TMAs). The final of 3 topic-specific resource sections provided contains links to a variety of publications about cardiorenal syndrome issues specific to atypical HUS.

RESEARCH by TOPIC

Note: These various links represent only a few of the publications about cardiorenal syndrome (CRS) available online.

Cardiorenal Syndrome: What is it, and how is it Treated?

Nephrology Hypertension Acute Kidney Injury: Cardiorenal Syndromes (acute decompensated heart failure and worsening renal function). Charytan D and McCausland FR, 2017. Renal & Urology News, Decision Support in Medicine.

Q & A Format, to include: What are the common presenting symptoms of cardiorenal syndrome type 1? What are the important points to focus on in the medication history? What tests to perform?

Cardiorenal Syndrome: The Clinical Cardiologists’ Perspective Chan EJ and Dellsperger K, 2011. Cardiorenal Med. 2011 Jan; 1(1): 13–22. doi: 10.1159/000322820

“The term ‘cardiorenal syndrome’, a relatively new term, refers to the interactivity between the cardiovascular and renal systems. Over the past decade, we have gained a better understanding of the relationship between these two organ systems. The initial definition of worsening renal function secondary to poor left ventricular function has advanced to a more current and sophisticated classification which attempts to relate the pathophysiology of cardiac and renal dysfunction and their interplay.” and

“From a cardiologist’s perspective, one thing remains clear. The management of the cardiorenal syndrome involves a multidisciplinary approach between cardiologists, nephrologists, and intensivists. Treatment needs to focus on the co-dependent relationship between these two vital organ systems.”

Therapeutic Options for the Management of the Cardiorenal Syndrome. Koniari K et al, 2010 Int J Nephrol. 2011; 2011: 194910.

“Patients with heart failure often present with impaired renal function, which is a predictor of poor outcome. The cardiorenal syndrome is the worsening of renal function, which is accelerated by worsening of heart failure or acute decompensated heart failure.” and

“The previous focus on symptomatic treatment with increasing doses of diuretics and vasodilators, which met resistance, is now fading. The new focus should be to recognize the cardiorenal syndrome, recognize it early and treat the whole patient for long term. The optimization of heart failure therapy also preserves kidney function. Novel therapeutic options may offer additional opportunities to improve volume regulation, while preserving cardiac and renal function. A close cooperation of cardiologists, nephrologists, and internists is required, as well as a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of the CRS, in order to establish an effective means of therapy in the future.”

Heart-Kidney Interaction: Epidemiology of Cardiorenal Syndromes (review article). Cruz DN and Bagshaw SM. International Journal of Nephrology, Vol, 2011, Article ID 351291

“Considerable data from observational studies and clinical trials have accumulated to show that acute or chronic cardiac disease can directly contribute to acute or chronic worsening kidney function and vice versa. The Cardiorenal Syndrome subtypes are characterized by important heart-kidney interactions that share some similarities in pathophysiology, however, appear to have important discriminating features, in terms of predisposing or precipitating events, risk identification, natural history, and outcomes.”

Cardiorenal Syndrome in Critical Care: The Acute Cardiorenal and Renocardiac Syndromes Cruz, Dinna N. , 2013. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease , Volume 20 , Issue 1 , 56 – 66.

“Heart and kidney disease often coexist in the same patient, and observational studies have shown that cardiac disease can directly contribute to worsening kidney function and vice versa. Cardiorenal syndrome (CRS) is defined as a complex pathophysiological disorder of the heart and the kidneys in which acute or chronic dysfunction in one organ may induce acute or chronic dysfunction in the other organ. This has been recently classified into five subtypes on the basis of the primary organ dysfunction (heart or kidney) and on whether the organ dysfunction is acute or chronic. Of particular interest to the critical care specialist are CRS type 1 (acute cardiorenal syndrome) and type 3 (acute renocardiac syndrome). CRS type 1 is characterized by an acute deterioration in cardiac function that leads to acute kidney injury (AKI); in CRS type 3, AKI leads to acute cardiac injury and/or dysfunction, such as cardiac ischemic syndromes, congestive heart failure, or arrhythmia. Both subtypes are encountered in high-acuity medical units; in particular, CRS type 1 is commonly seen in the coronary care unit and cardiothoracic intensive care unit.”

Pathophysiology of the cardio-renal syndromes types 1–5: An uptodate DiLullo L et al, 2017. Indian Heart Journal. Vol 69, Issue 2, Mar–Apr 2017.

“The pathophysiology and clinical impact of the various subtypes of cardiorenal syndrome exemplify the intricate cross talk between the heart and the kidney. Given the huge morbidity and mortality of the dual burden of these organ system afflictions, early recognition of the clinical phenotype of cardiorenal syndrome and interventions to slow down end organ damage are crucial in positively influencing the burden of this pathological symbiosis.”

Classification and Pathophysiology of Cardiorenal Syndrome, an ASN Resource. Kidney News » Special Sections » The Kidney Cardiac Link

Acute Cardiorenal Syndrome: Classification Types 1 – 5

*Acute cardiorenal syndrome (type 1): Acute worsening of heart function leading to kidney injury and/or dysfunction

*Chronic cardiorenal syndrome (type 2): Chronic abnormalities in heart function leading to kidney injury and/or dysfunction

*Acute renocardiac syndrome (type 3): Acute worsening of kidney function leading to heart injury and/or dysfunction

*Chronic renocardiac syndrome (type 4): Chronic kidney disease leading to heart injury, disease, and/or dysfunction

*Secondary cardiorenal syndrome (type 5): Systemic conditions leading to simultaneous injury and/or dysfunction of heart and kidney

“Cardiac and renal diseases are common and frequently coexist, adding to the complexity and costs of care, and ultimately, to increased morbidity and mortality (1). A consensus conference on cardiorenal syndromes (CRS) was organized under the auspices of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) in Venice, Italy, in September 2008 to develop a classification scheme to define critical aspects of CRS.

After three days of deliberation among 32 attendees, summary statements were developed, defining CRS as disorders of the heart and kidneys whereby acute or chronic dysfunction in one organ may induce acute or chronic dysfunction of the other. The plural form indicates the presence of multiple subtypes of the syndrome and recognizes the bidirectional nature of the various syndromes. The subtypes recognize the primary organ of dysfunction (cardiac versus renal) in terms of importance and by temporal sequence and timeframe (acute versus chronic).”

Dialysis & Cardiorenal Syndrome

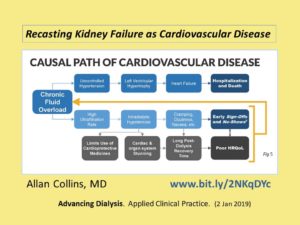

Recasting Kidney Failure as Cardiovascular Disease Collins, Allan. Advancing Dialysis. Applied Clinical Practice. 2 Jan 2019

“Chronic fluid overload leads to a cascade of uncontrolled hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, and heart failure. In turn, we observe frequent arrhythmias and high incidence of sudden cardiac death.”

Cardiorenal Syndrome in End-Stage Kidney Disease Tsuruya K et al, 2015. Blood Purif. 2015;40(4):337-43. doi: 10.1159/000441583.

“Cardiorenal syndrome (CRS) in patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) represents mainly cardiovascular disease (CVD) due to various complications associated with renal dysfunction-defined as type 4 CRS by Ronco et al.-because the effect of cardiac dysfunction on the kidneys does not need to be taken into consideration, unlike in non-dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease (CKD).”

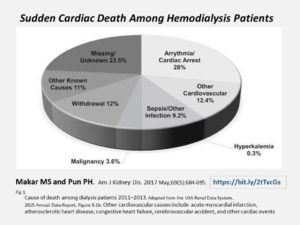

Sudden Cardiac Death Among Hemodialysis Patients Makar MS and Pun PH (2017). Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 May;69(5):684-695.

“Hemodialysis patients carry a large burden of cardiovascular disease; most onerous is the high risk for sudden cardiac death. Defining sudden cardiac death among hemodialysis patients and understanding its pathogenesis are challenging, but inferences from the existing literature reveal differences between sudden cardiac death among hemodialysis patients and the general population. Vascular calcifications and left ventricular hypertrophy may play a role in the pathophysiology of sudden cardiac death, whereas traditional cardiovascular risk factors seem to have a more muted effect. Arrhythmic triggers also differ in this group as compared to the general population, with some arising uniquely from the hemodialysis procedure.”

aHUS & Cardiorenal Syndrome

Cardiovascular complications in atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome Noris M, Remuzzi G. (2014) Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014 Mar;10(3):174-80

(As opposed to Haemolytic uraemic syndrome or HUS caused by shiga toxin-producing bacteria)

“Atypical HUS (aHUS) accounts for 10% of cases and has a poor prognosis. About 60% of patients with aHUS have dysregulation of the alternative complement pathway (complement-mediated aHUS). The kidney is the main target organ, but other organs might also be affected. Cardiac complications occur in 3–10% of patients with complement-mediated aHUS, as a consequence of microangiopathic injury in the coronary microvasculature, and can cause sudden death. Emerging evidence also suggests that either thrombosis or stenosis of the medium and large arteries might complicate disease course, and such disorders occur even after renal function is lost.”

Atypical Hemolytic‐Uremic Syndrome: An Update on Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Raina, R, Krishnappa, V, Blaha, T, Kann, T, Hein, W, Burke L. and Bagga A. (2019). Ther Apher Dial, 23

“Approximately 10% of patients show complications such as myocardial infarction, myocarditis, heart failure, cardiomyopathy, and occlusive coronary artery disease. Patients with mutations in CFH and C3 show high risk of involvement of the coronary vasculature.”

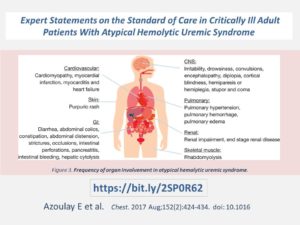

Expert Statements on the Standard of Care in Critically Ill Adult Patients With Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Azoulay E et al, 2017. Chest. 2017 Aug;152(2):424-434. doi: 10.1016

“Acute kidney injury is common in aHUS, but other organ involvement, including cardiac, gastrointestinal, or neurological damage, may be present and can dominate the clinical picture”

“Neurologic signs (eg, confusion, focal cerebral abnormalities, seizures) and cardiovascular signs (eg, cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, myocarditis, heart failure) occur in 10% to 48% and 10% of aHUS cases, respectively; however, these signs tend to be more frequent in TTP. Tsai reported that complications of abnormal vascular permeability (including brain edema, pleural or pericardial effusions, pulmonary edema from oliguria or cardiac insufficiency, and ascites) may be used to differentiate TTP from aHUS because they are thought to occur rarely in TTP without comorbidity. aHUS is also occasionally associated with large artery obstruction. “

Chronic Kidney Disease, Hypertension and Cardiovascular Sequelae during Long Term Follow up of Adults with Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Chaturvedi S et al (2018) ASH presentation: Oral and Poster Abstracts 3 Dec 2018.

“One patient died due to a myocardial infarction during the aHUS episode.

Of the 44 survivors, 15 (34.1%) had complete renal recovery, 9 (20.5%) had chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 1-4, and 20 (45.5%) developed CKD stage 5 requiring dialysis at 3 months after the acute episode. Fifteen patients underwent subsequent renal transplantation.” and

“Thirty-one (70.4%) were on antihypertensive therapy, and 67% (21 of 31) of these were not controlled to <140/90 mmHg despite the use of multiple agents (Figure 1C). Echocardiograms were performed in 29 (64.4%) individuals (12 within 3 months of diagnosis, and 17 after 3 months). Of these 17, 29.4% were normal studies, 23.5% had reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, 29.4% demonstrated left ventricular hypertrophy or diastolic dysfunction, and 11.7% had pulmonary hypertension.” and

“CONCLUSION: Malignant hypertension and cardiac involvement are common during acute aHUS. aHUS survivors also have a high prevalence of hypertension, including a notable incidence of new onset as well as uncontrolled hypertension following aHUS diagnosis. CKD is present in the majority of survivors, and structural cardiopulmonary disease is common. Complement activation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Further investigation is needed to evaluate the epidemiology of cardiovascular sequelae in aHUS, their associations with specific complement mutations, and optimal management.”

Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Presenting as Acute Heart Failure-A Rare Presentation: Diagnosis Supported by Skin Biopsy. Kichloo A et al (2019) J Investig Med, High Impact Case Rep. 2019 Jan-Dec;7:2324709619842905

“The incidence rate of aHUS in the United States is about 2 per million. The kidney is the most commonly involved organ, although extrarenal manifestations are observed in 20% of the patient most of which involving the central nervous system, with relatively rare involvement of heart. Probable causes include high-output heart failure from anemia and microangiopathic injury in the coronary vasculature resulting in varying manifestations ranging from myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, to acute decompensated heart failure.”

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: what is it, how is it diagnosed, and how is it treated? Nester CM and Thomas CP (2012) Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2012;2012:617-25. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.617.

“Marked hypertension may also be present either from the acute kidney injury or from the ischemia caused by the TMA. Hypertension may be severe enough to provoke posterior reversible encephalopathy or cardiac failure.” and

“Myocardial infarction due to cardiac microangiopathy has been reported in approximately 3% of patients and is presumed to be the cause of reported episodes of sudden death.”

Acute Systolic Heart Failure Associated with Complement-Mediated Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Vaughn JL, Moore JM, Cataland SR (2015). Case Rep Hematol. 2015; 2015: 327980.

“Complement-mediated hemolytic uremic syndrome (otherwise known as atypical HUS) is a rare disorder of uncontrolled complement activation that may be associated with heart failure. “ and

“Our case report provides evidence that patients with complement-mediated HUS and acute heart failure treated with eculizumab may recover cardiac function over time. Although our patient decompensated the requiring transfer to the medical intensive care unit and a prolonged hospitalization, her cardiac function gradually improved and she returned to her previous functional state. Her slow recovery despite eculizumab therapy was likely secondary to her acute heart failure.

The pathophysiology of acute heart failure in patients with thrombotic microangiopathies remains undefined. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed including high output heart failure secondary to anemia and myocardial ischemia secondary to microvascular thrombi. In complement-mediated HUS, increased complement activation interferes with endothelial resistance to thrombosis, which may contribute to the formation of microvascular thrombi [6]. Our patient had evidence of a Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, which is a poorly understood cardiomyopathy that often presents with signs and symptoms of myocardial infarction without demonstrable obstructive coronary artery disease. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy may be partly due to microvascular dysfunction.”

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome presenting as myocarditis and cardiogenic shock in an adult Melody Hermel et al, 2018. Journal of the American College of Cardiology Mar 2018, 71 (11 Supplement) A2358 DOI: 10.1016

“aHUS is a complement-mediated disease characterized by hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia and acute kidney disease. Only a limited number of cases of cardiovascular involvement in HUS related to infection have been described in children. When clinically indicated, pursuing a renal biopsy can help promptly diagnose and guide appropriate therapy. This is the first known report of aHUS – confirmed by a renal biopsy – presenting with myocarditis and cardiogenic shock in an adult.”

Myocardial infarction is a complication of factor H-associated atypical HUS Sallée M, Daniel L et al. NephrolDial Transplant. 2010;25:2028-2032.

“We describe the case of a 43-year-old woman who was diagnosed with an atypical haemolytic–uraemic syndrome (aHUS) associated with a pathogenic mutation in the factor H gene (C623S). After 15 days of treatment, she suffered a sudden cardiac arrest and died despite intensive resuscitation attempts. She showed only one cardiovascular risk factor, hypercholesterolaemia. Her sudden death was secondary to cardiac infarction related to a coronary thrombotic microangiopathy. This is the first case of aHUS related to a mutation in the factor H gene associated with cardiac microangiopathy. This case emphasizes the need to screen for cardiac complication during the treatment of aHUS.”

Heart disorders in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in children Khadizha E et al, 2017. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 32, Issue suppl 3, 1 May 2017

“Cardiovascular manifestations of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) include the development of cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, myocardial manifestations, occlusion of coronary vessels, heart failure. They occur in 10-43% of patients with aHUS and can cause adverse outcomes.” and

“CVC in the acute phase of aHUS were detected in 22 (67%) patients: arterial hypertension (AH) in 22 (67%), dilatation of the left ventricle (DLV) – 15 (45%), reduced ejection fraction (EF) in 9 (27%), ischemic manifestations in 3 patients (9%). 7 (21%) patients received cardiac glycosides for 1-48 months. CVC associated with severity of acute kidney injury (AKI): 18 of 23 (78%) children received RRT and 4 of 10 (40%) of the children did not need RRT (p<0.05). Among patients with aHUS presented in 2012 CVC were detected more often than in the group of children who became ill after 2012, because of access to eculizumab: 85% vs 50% (p<0.05).” and

“CONCLUSIONS: CVC is a frequent extrarenal manifestation of aHUS. Development of CVC in the acute period is associated with a severe AKI, chronic CVC – with the formation of CKD. High frequency of chronic CVC in children with severe AKI associated with aHUS highlight the need to timely appointment of targeted therapy.”

Recovery of renal function after long-term dialysis and resolution of cardiomyopathy in a patient with aHUS receiving eculizumab Khadizha E et al, 2016. BMJ Case Rep 2016 Feb 15 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-213928

“We present the case of a 18-month-old girl with renal and cardiac manifestations of atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome (aHUS), and a novel complement factor H mutation. Transient haematological remission was achieved with intensive plasmapheresis, but cardiac function deteriorated and renal function was not restored.” and

“Earlier initiation of eculizumab, however, might have prevented the irreversible renal sclerosis and cardiac dysfunction.”

Complement factor B mutation-associated aHUS and myocardial infarction Noronha N et al, 2017. BMJ Case Rep. 2017 Jul 14;2017. doi: 10.1136.

“A 6-month-old female infant was referred with a 3-day history of low-grade fever, slight nasal congestion and rhinorrhoea. On admission, the clinical findings were unremarkable and she was discharged home. However, she became progressively more listless with a decreased urine output and was once again seen in the emergency department. Analytically she was found to have metabolic acidosis, hyperkalaemia, thrombocytopaenia, anaemia and schistocytes in the peripheral blood smear. Based on these findings, the diagnosis of haemolyticâ-uremic syndrome was made. A few hours postadmission, there was an abrupt clinical deterioration. She went into cardiorespiratory arrest and she was successfully resuscitated. An ST-segment elevation was noted on the ECG monitor and the troponin I levels were raised, suggesting myocardial infarction. Despite intensive supportive therapy, she went into refractory shock and died within 30 hours.”

Myocardial infarction is a complication of factor H-associated atypical HUS Sallée M et al, 2010. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010 Jun;25(6):2028-32. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq160

“Cardiac complications are frequently seen in thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura related to ADAMTS13 deficiency. We describe the case of a 43-year-old woman who was diagnosed with an atypical haemolytic-uraemic syndrome (aHUS) associated with a pathogenic mutation in the factor H gene (C623S). After 15 days of treatment, she suffered a sudden cardiac arrest and died despite intensive resuscitation attempts. She showed only one cardiovascular risk factor, hypercholesterolaemia. Her sudden death was secondary to cardiac infarction related to a coronary thrombotic microangiopathy. This is the first case of aHUS related to a mutation in the factor H gene associated with cardiac microangiopathy. This case emphasizes the need to screen for cardiac complication during the treatment of aHUS.”

Thrombomodulin and Endothelial Dysfunction: A Disease-Modifier Shared between Malignant Hypertension and Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Demeulenaere M et al, 2018. Nephron. 2018;140(1):63-73. doi: 10.1159.

“Outcome of the TM-associated aHUS is relatively poor with frequent relapses after transplantation despite its membrane-bound character. We observed a woman presenting with malignant hypertension (MHT) and associated kidney, brain, cardiac, and hematological involvement with thrombotic microangiopathy on kidney biopsy. She had a documented mutation of the gene coding for TM, which was associated with both aHUS and an increased risk for venous and arterial thrombosis. “

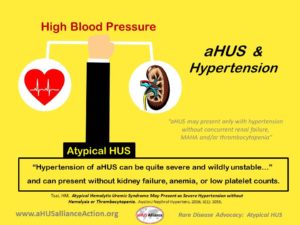

Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome May Present as Severe Hypertension without Hemolysis or Thrombocytopenia Tsai HM (2016) Austin J Nephrol Hypertens. 2016; 3(1): 1055.

“Hypertension of AHUS can be quite severe and wildly unstable, presumably due to the dynamic and often transient nature of acute lesions of TMA. When the sites of endothelial injury are few but happen to affect preglomerular hemodynamics, the pathology may be sufficient to cause abnormal renin release and hypertension but inadequate to cause renal insufficiency, MAHA or thrombocytopenia. Hence, AHUS may present only with hypertension without concurrent renal failure, MAHA and/or thrombocytopenia.”

(Image above created by the aHUS Alliance)

L Burke, March 2019