As scientific discoveries advance, knowledge gaps slowly get smaller as well. This is true for any medical condition, but especially important for rare diseases like aHUS (atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome). Only about 5% of rare diseases have an approved treatment or therapy, among them is atypical HUS with its patient population numbering only a handful of people per million (estimates vary, 2 to 9 patients per million population).

Despite almost 2 decades of medical appointments and acute phases of aHUS activity for two family members, a family recently shared their new knowledge about a visual exam experienced during a hospital stay for their older teen. Actually, it’s more about ‘connecting the dots’ between bits of aHUS information and suddenly seeing a bigger picture.

Never before had they experienced a clinician checking soft tissues of the eyes and mouth during their daily hospital rounds. Yes, they’ve been aware for years that people diagnosed with atypical HUS can experience vision issues (see aHUS & eyes article) and that there is an established connection between eye and kidney health (The Eye/Kidney Connection, 2021). In over 20 years of family members’ aHUS treatment they had not experienced a nephrologist conducting a visual exam of the eye during hospital medical rounds.

It was a ‘teachable moment’, and the medical provider making the request was happy to take time to explain when asked for a post-exam explanation. It was on the pediatric floor of a well-regarded hospital, but the doctor’s request had been unusual, “I’m going to ask you to make a couple of funny faces, so I can take a good look at your eyes and in your mouth.” Why, they wondered? How can ‘funny faces’ possibly be something to monitor health and in turn inform aHUS patient care?

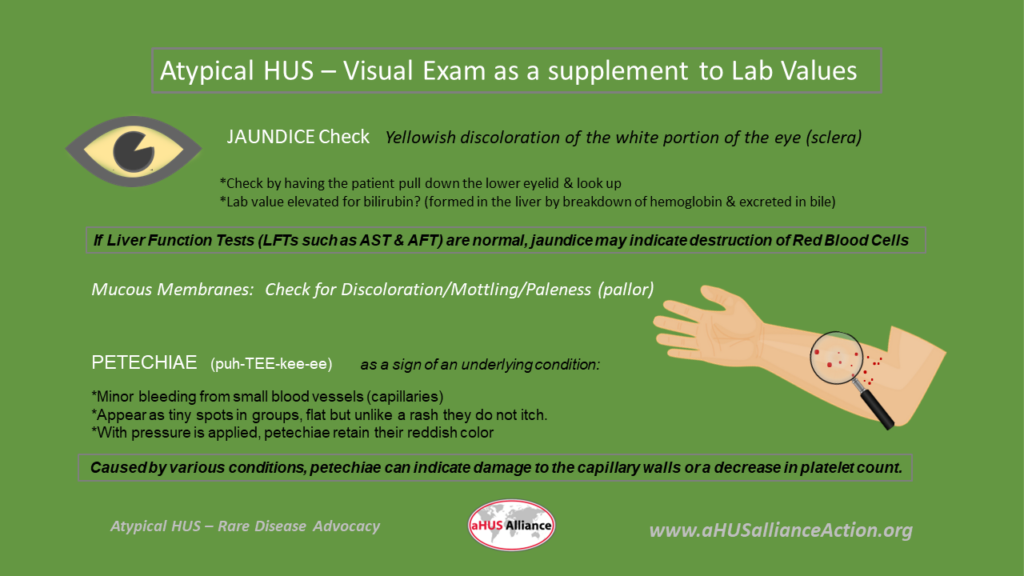

The family was familiar with the term ‘jaundice’ (hyperbilirubinemia) and how it can cause skin or whites of the eyes to turn yellow, often due to liver disease or certain illnesses. What was the family’s new information, and how did all the pieces fit together? Jaundice occurs when the liver cannot process bilirubin effectively, and this can be observed not only in the skin and eye areas but also seen in mucous membranes. Abnormal rates for destruction of red blood cells can cause jaundice. Now a clearer picture formed, since the family already knew that aHUS causes the lining of blood vessels to shear apart red blood cells. Confirming visible signs of aHUS activity, in supporting evidence of lab test values, was in part the rationale behind why the physician asked the patient to pull down his lower eyelid for her close inspection. A scan of the patient’s skin was also conducted, but it turns out there was a bit more to that as well.

Next was a visual scan of the arms and legs. Then on to the other ‘make a funny face’, a request to open the mouth while also asking the patient to pull down the lower lip. Why? The skin and body’s soft tissue can be observed for paler than normal coloration (tissue pallor) and for tiny flat spots called ‘petechiae’. Petechiae (puh-TEE-kee-ee) are often found in groups, may appear to be rash-like but they do not itch and they maintain their reddish color despite any applied pressure. Petechiae can form when blood capillaries leak blood under the skin or mucous membranes (such as in the mouth) and which cause pinpoint discoloration. Yet another visual clue for clinicians examining aHUS patients, checking for unusual tissue pallor as well as for the presence of petechiae.

We appreciate being able to share their story with other aHUS families, as it points out that there’s always something more to learn about atypical HUS. Maybe medical professionals don’t often hear how important their time and explanations are to patients and to family caregivers. It is, and we applaud the clinicians who make the extra effort to help us better understand our condition.

While it’s interesting to learn about the experiences of aHUS families, perhaps even more meaningful is how shared experience can serve to ‘connect the dots’ and bring new insights. We hope that as other aHUS families share their experiences, it can serve to illuminate the patient journey and help create better understanding of what it’s like to meet the challenges of being diagnosed with atypical HUS.