We marked aHUS Awareness Day (24 Sept) with our own advocacy-based research, releasing the 1st report of data and insights from aHUS Alliance Global Action team on the 2021 global survey of aHUS patients’ experiences about the diagnostic process (Links: Survey, Background, Report). Whether by serendipity or considerate design, the team of aHUS researchers and clinical care at the Mario Negri Institute in Bergamo Italy marked aHUS Day with release of an updated version of what we consider the ‘book of aHUS’, GeneReviews®: Genetic Atypical Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome (Authors: Marina Noris, Elena Bresin, Caterina Mele, and Giuseppe Remuzzi).

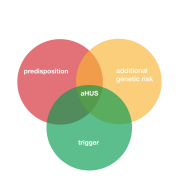

Much remains unknown about how certain circumstances regarding genetics and environmental factors may combine to trigger atypical HUS disease activity, such as: infections (bacterial/viral), pregnancy, certain drugs, organ transplantation, cancer, and inflammation or chronic/autoimmune disease impact. Highlights of recent research here include our brief snapshots of publications that touch upon varied medical issues which provide a spotlight for atypical HUS. These include consideration of triggers for aHUS activity, diagnosing and treating atypical HUS in pregnancy, and sorting through multiple organ complications of TMA to determine how/where aHUS is an underlying, secondary, or causal factor.

New research on topics such as thrombotic microangiopathy and complement-mediated diseases serve to also shed light on atypical HUS diagnosis and treatment. We’re pleased to note that one previously delayed conference focusing on aHUS has been rescheduled, to be held in Bergamo Italy on 23-25 June 2022. Hosted by ISN and the Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, the symposium topic is Complement-mediated Kidney Diseases: Classification, Genetics, and Treatment.

How is it helpful to see atypical HUS in the context of an expanded, broader ‘knowledge pool’? Research into COVID-19 infection includes insights into inflammation, complement activation, and thrombotic microangiopathy (damage from tiny clots in small blood vessels throughout the body). That information does more than lead to a better understanding of COVID-19 issues and care, since expanded knowledge about the complement system (part of the body’s immune response) touches upon several key issues related to aHUS. (FMI: see our aHUS & COVID-19 Resource Page)

The current trend developing in aHUS research is diving deeper into subtypes of atypical HUS and its triggers and/or clinical presentations. The National Kidney Foundation has launched an international panel of specialists to help determine classification of atypical HUS within the wider fields of thrombotic microangiopathy and complement research (See our story on the aHUS Nomenclature Project group). Terminology has been increasingly difficult to sort through and differentiate, which can have the undesired effect of fragmenting aHUS information. Atypical HUS may occur secondary to other medical history, such as postpartum aHUS or in the event of an over-active immune response as with the multi-organ involvement due to COVID-19 or with streptococcal pneumonia infection.

As new research and information becomes available, it seems to be intertwined in a way that begs the question, “ What type of aHUS are we looking at?” We’re here to help. Cutting through the confusing terminology and classification system in need of an update, the aHUS Alliance Global Action team offers this selection of highlights from the last month or two of atypical HUS research. With more than 800 unique entries in our online ‘library’ for aHUS-specific publications, we invite you to view categories for additional research regarding Diagnosis, Treatment, Pregnancy, Transplant, Multi-Organ Involvement, Triggers & more – view it HERE.

Treatment & Triggers

There’s been a recent increase in aHUS research on topics of high interest. Our website features original content articles from the patient viewpoint such as: considerations to be discussed by patient and physician regarding duration of treatment, the lack of specific guidelines for aHUS patient monitoring after treatment ends, and what’s involved when switching from eculizumab to ravulizumab.

It’s helpful to have a ready explanation of aHUS medical terminology within the updated and comprehensive GeneReview® (Noris et al, 2021), and it’s encouraging that the NFK project will re-examine current atypical HUS nomenclature and classification. A new era seems to be approaching regarding subtypes of atypical HUS, which in turn will affect diagnosis as well as treatment and disease management. Terminology and classification can impact information flow, as noted in this selection of new research.

Even as patients and physicians focus questions surrounding drug cost and access, as well as ‘the right treatment for the right amount of time’, researchers recently illuminated these treatment concerns to include the many complexities of accurate diagnosis of atypical HUS. Often there are diagnostic dilemmas to unravel before appropriate care plans can be determined. Concerns with supply chain for aHUS therapeutic drugs might have been impacted by economic, transportation or drug distribution, or workplace/manufacturing issues due to COVID-19 which has added a new twist.

Neto et al. Eculizumab interruption in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome due to shortage: analysis of a Brazilian cohort “We included patients with aHUS whose eculizumab therapy underwent unplanned discontinuation for at least 30 days between January 1st, 2016 and December 31st, 2019 during the maintenance phase of treatment” and “We analyzed 25 episodes of exposure to risk of relapse, from 24 patients.”, to find “the cumulative incidence of aHUS relapse at 397 days was 58% after eculizumab interruption.”

Abbas et al. De Novo and Recurrent Thrombotic Microangiopathy After Renal Transplantation: Current Concepts in Management “Unfortunately, the successful use of the biological agent eculizumab, an anti-C5 agent, in some of these syndromes is largely impeded by its high cost, which is linked to its use as a life-long therapy. However, newly suggested therapeutic options may ameliorate this drawback.”

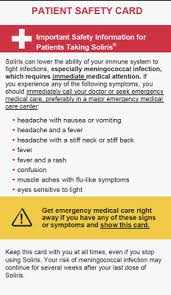

Prior to starting a therapeutic course of eculizumab or ravulizumab to treat aHUS, meningococcal vaccines are given to reduce the increased risk that accompanies these complement inhibitors.

Ispasanie et al. Alternative Complement Pathway Inhibition Does Not Abrogate Meningococcal Killing by Serum of Vaccinated Individuals. Stating “vaccination can provide protection against invasive meningococcal disease in patients treated with alternative pathway inhibitors.”, this paper notes why concern and recommendation for meningococcal vaccines exists. “Neisseria meningitidis is a Gram-negative bacterium, also called meningococcus, which asymptomatically colonizes the nasopharyngeal mucosa of 5-10% of the adult population. Colonization mostly induces immunity with protective antibody response, but in rare cases the meningococci can gain access to the circulation and may cause systemic disease such as sepsis and meningitis”.

We’re starting to see more publications dealing with aHUS patients making the “switch” from eculizumab (brand name Soliris) to ravulizumab (brand name Ultomiris), both biopharmaceuticals from Alexion, Astrazena Rare Disease. We’ve reported on UK’s switch guidelines which were posted on the National aHUS Service, view that article HERE.

Ehren et al. Real-world data of six patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome switched to ravulizumab

Alhabhbeh et al. Rare Presentation of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome in an Adult Instead of platelets being consumed by the formation of tiny clots, as well as low red blood cell and hemoglobin levels associated with aHUS activity, the patient had normal hemoglobin levels and only slightly low platelet counts. “These wide variations in clinical presentation underscores the variability of patient profiles and points out how vital it is to have more clear diagnostic criteria for aHUS”.

Wang et al. Streptococcal pneumonia continues to be an uncommon but important cause of HUS.

This paper presents the concept that streptococcal pneumonia is rare cause of HUS, and utilizes a classification abbreviation not often seen. “The occurrence of Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome (SP-HUS) is increasing.” and states,“Among children with HUS, approximately 5% have SP-HUS, with 38%-43% of atypical HUS cases being SP-HUS.”

It’s not known what ‘perfect storm’ of conditions might combine to activate an atypical HUS episode for any given individual, in any particular situation, at any set point in time. With atypical HUS, the body’s immune response becomes over-activated, which can be caused by infection, inflammation, certain drugs, pregnancy, or other factors. Since COVID-19 is an illness caused by the SARS-CoV2 virus, there’s recent research regarding cases where it has triggered aHUS.

Here are 5 articles with the common topic of aHUS and COVID-19, but 3 of the 5 employ differing key terms that may cause these publications to be somewhat overlooked in the aHUS community.

El Sissy et al. COVID-19 as a potential trigger of complement-mediated atypical HUS. Click to view the pdf. FMI, read the aHUS Alliance article on the topic aHUS described as CM-TMA.

Gill et al. COVID-19-associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and use of Eculizumab therapy

Kaufeld et al. Atypical Hemolytic and Uremic Syndrome Triggered by Infection With SARS-CoV2

Utebay et al. Complement inhibition for the treatment of COVID-19 triggered thrombotic microangiopathy with cardiac failure: a case report Great flowchart, view Figure 2. “This group has been re-named from atypical (a)HUS into complement-mediated TMA (cTMA).” Note the heart involvement due to TMA.

Weinbrand-Goichberg et al. COVID-19 in children and young adults with kidney disease: risk factors, clinical features and serological response Look closely at Table 1: Patients Clinical Characterististics, to find 4 aHUS patients combined with other conditions phrased under the group name of “glomerular disease”.

Pregnancy

Pregnancy is an exciting time for families who are expecting, but atypical HUS can cause complications during and/or after the pregnancy. The aHUS Patient Research Agenda listed family planning concerns as one of its 15 central questions (section 5, item 2). Given the many changes for women who are expecting, it’s difficult for their obstetrics team to figure out whether it’s another medical condition (such as pre-eclampsia or HELLP syndrome) or a diagnosis of aHUS. “Atypical HUS is a ‘diagnosis of exclusion’, referring to the concept that diagnosis of aHUS is what remains after other medical conditions are ruled out.

“Pregnancy-associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a life-threatening thrombotic microangiopathy which may be mistaken for hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome. We sought to identify laboratory parameters that differentiate aHUS and HELLP syndrome in the postpartum period.” Distinguishing aHUS apart from HELLP or pre-eclampsia is central to accurate and rapid treatment to address complex issues, both during pregnancy and following delivery.

Atypical HUS activity can cause damage to any organ throughout the body, as tiny clots in small blood vessels may form to negatively affect organ function. Here’s a case study regarding clotting which severely impacted lung function, to note that with pregnancy-related complications an aHUS diagnosis should be considered.

Ketenciler et al. Successful treatment of massive pulmonary embolism in a pregnant woman complicated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome

“The treatment of the massive pulmonary embolism concomitant hemodynamic instability in pregnancy is difficult and controversial and carries a high risk for both the baby and the mother.”

The title says it all for this case study which follows the pregnancy of a liver-transplant patient. Questions arise on whether this could be drug-induced TMA and whether liver transplantation and pregnancy affect complement production.

Interestingly, co-author Kate Bramham of King’s College Hospital and King’s College London, addressed the topic of aHUS and pregnancy at a Thrombosis UK symposium. Click HERE to watch her 23 minute presentation on our Atypical HUS Clinical Channel on YouTube.

Family planning is multi-faceted for anyone, but even more factors need to be considered for women who have had a kidney transplant. Preplanning discussions prior to pregnancy are essential.

Ponticelli et al. Planned Pregnancy in Kidney Transplantation. A Calculated Risk

“Pregnancy is not contraindicated in kidney transplant women but entails risks of maternal and fetal complications. Three main conditions can influence the outcome of pregnancy in transplant women: preconception counseling, maternal medical management, and correct use of drugs to prevent fetal toxicity.”

Following the full text April 2021 information on aHUS and pregnancy by Fakouri et al with data from the aHUS Global Registry, here’s another publication on pregnancy from this registry.

Rondeau et al. Pregnancy in Women with Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

“As of April 1, 2019, 44 pregnancies were recorded in 41 patients, with 24 pregnancies exposed to eculizumab. Pathogenic variants were identified in 48.8% of patients. Three patients were on dialysis and 6 patients had a kidney graft at the time of pregnancy. Excluding elective terminations, 85.3% of pregnancies resulted in live births. Elective terminations were recorded in 22.7% of pregnancies, miscarriages occurred in 9.1% of pregnancies, and late fetal death in 2.3% of pregnancies. No malformations or anomalies were reported.” and “Conclusions: Our results show that in women with aHUS, even on dialysis or with a kidney graft, pregnancy is possible with careful monitoring for aHUS flares and prematurity.”

Our website features scores of original articles on the topic of atypical HUS and pregnancy, such as aHUS Pregnancy Counselling, as well as other high interest topics which uniquely provide a family perspective while expounding upon current research. The aHUS Alliance Global Action team encourages researchers to release their studies and publications in full text versions, with Open Access to facilitate sharing knowledge. Additionally, we welcome and applaud those individuals and groups who include “Plain Language Versions” as part of their publication’s Supplementary Materials.

Are you staying current with aHUS research & News?

We invite you to subscribe to our free newsletter, The aHUS Global Advocate

For More about our Newsletter & reasons to Stay Connected

Click Here to Sign Up to receive the Newsletter

Article No 469