The diseases PNH and aHUS, although different, share features in common. Both are very rare, both are the result of uncontrolled complement and both can benefit from complement inhibitor treatment.

The damage to red blood cells in PNH is the result of direct destruction of those cells by complement’s membrane attack complex as it is designed to do.

In aHUS red blood cell damage is an indirect result from complement because of thrombotic microangiopathy, or TMA blocking up the capillaries and blood cells break under the shear stress of getting through them.

And that was the difference. Until very recently.

Then Associate Professor Nick Burwick of The University Washington posted something on X that PNH could also be a TMA. Global Action offered Nick the platform to explain why this may be the case and its implications for patients.

Atypical HUS and PNH: better together?

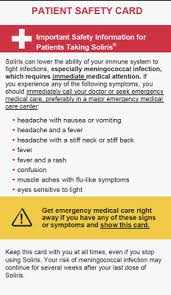

There are two patients, Ash and Dash. Ash and Dash both presented to their local hospital for symptoms of increasing fatigue, abdominal pain, and onset of brownish coloured urine. Both Ash and Dash were found to have hemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia. As you can imagine, doctors were perplexed at these two patients with similar symptoms and similar names. Fortunately, there were some distinguishing features. Ash had normal kidney function, but a large blood clot occluding the portal vein. Dash had acute kidney injury with no evidence of portal vein thrombosis, but thrombotic disease in the kidney. Under the microscope, Ash’s red blood cells looked fairly normal, while Dash had red blood cells that were fragmented. After some additional diagnostic testing, they were both diagnosed with complement-mediated disorders and prescribed the same medication, a monoclonal antibody targeting complement protein C5. The treatment turned out to be very effective for both.

Ash was diagnosed with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), Dash with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS).

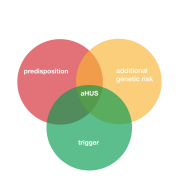

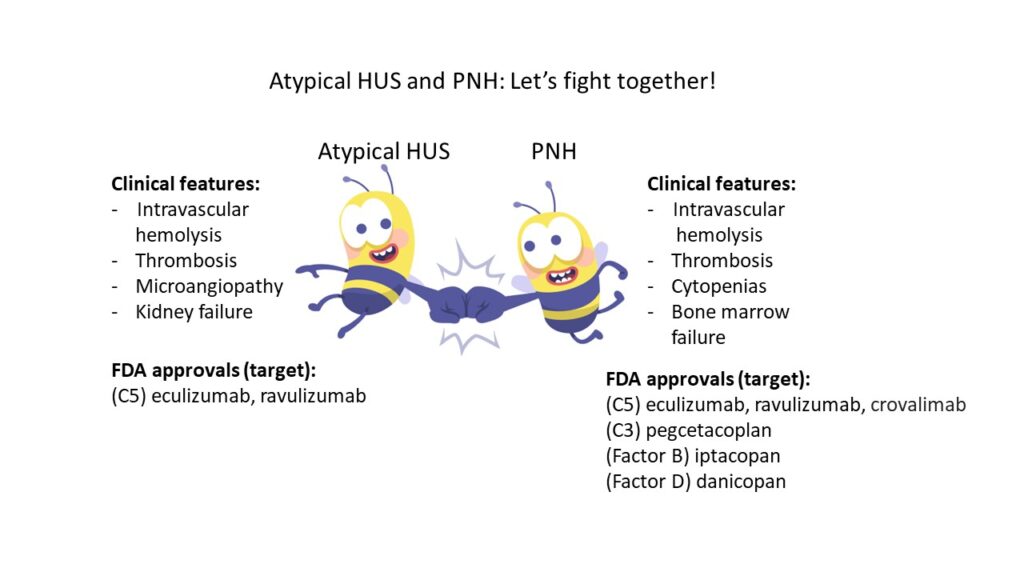

The clinical presentation and treatment approach for these two disorders can look very similar on the surface, so it is important to understand a little more about PNH, a disease which may be less familiar to the aHUS community. PNH is a rare clonal blood disorder that affects an estimated 1.5 per 100,000 persons globally (1). PNH is characterized by intravascular hemolysis, venous and arterial thrombosis (venous > arterial), cytopenias, and bone marrow failure. In contrast to PNH, thrombotic microangiopathy disorders (TMAs) such as aHUS, are defined broadly by the presence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and end-organ ischemic injury. Despite this definition, the clinical phenotype of specific TMA disorders is variable, with distinct disease drivers. PNH shares overlapping features with recognized TMA disorders, but with some key clinical differences, and distinct genetic underpinnings. PNH is associated with acquired mutations in the X-linked gene PIGA which leads to reduced or absent expression of GPI anchored proteins on the surface of hematopoietic cells. Specifically, it is the loss of GPI-anchored complement regulatory proteins CD55 and CD59 on the red blood cell (RBC) surface, that lead to increased RBC sensitivity to complement-mediated hemolysis (2). Loss of CD55/CD59 and other GPI-anchored proteins can also lead to dysfunction of white blood cells and platelets, further contributing to vascular inflammation, platelet activation and thrombosis (3).

When we look at these two disorders through the lens of the physician, we can imagine the hematology doctor going down to look at the peripheral smear under the microscope. This is a very practical diagnostic step for the physician, which can’t be overlooked. At this point in time, the physician may not have much specialized diagnostic or pathologic results available, and there may be some urgency to making an initial treatment decision. The presence of shistocytes would suggest fragmentation hemolysis and provide support for a thrombotic microangiopathy, while the lack of shistocytes might steer the physician away from a TMA-mediated process. The presence of shistocytes on peripheral smear is not a cardinal feature of PNH. However, it should be appreciated that historically, it is not uncommon for PNH patients to develop kidney injury. In one study, advanced kidney disease (stage 3-5), was identified in 21% of patients (4). The pathophysiology of PNH mediated kidney disease may reflect factors including exposure to cell free hemoglobin, tubulointerstitial inflammation, and/or microvascular thrombosis. PNH can also present with stroke (5).

Taking a step back, and now looking through the lens of a patient, we can see how patient advocates like Ash and Dash might spot their disease similarities and wonder why patient focused groups, pharmaceutical companies, and academicians for the two disorders couldn’t come together in a more unified way, to leverage shared resources and disease-specific knowledge to accelerate research and disease awareness. Given the shared role of complement in both disorders, interests would be aligned towards accelerating clinical trial advancements, FDA approval of new drugs, and funding for basic and translational research. Would aHUS and PNH be better off together? Additional FDA approved agents for PNH including the pegylated C3 inhibitor pegcetacoplan, the factor B inhibitor iptacopan, and factor D inhibitor danicopan, show the success of clinical trials targeting the PNH population. In this sense, approvals for aHUS patients have lagged significantly behind. These are different diseases, with unique diagnostic and treatment challenges, but the difference in FDA approvals is notable.

The way we categorize PNH within the broader taxonomy of blood disorders is important, since grouping PNH within similar disease entities could help consolidate efforts among rare disease advocates. Classic hemolytic PNH, which is the focus of this article, is rarely mentioned within the context of TMA disorders. To classify PNH as a PNH-TMA in the nomenclature would, however, require an acknowledgement that we need a broader definition of what a TMA is. Given the association of PNH with bone marrow failure, PNH is also quite unique among the hemolytic-thrombotic disorders, with a lot at stake for patients. Synergy between the PNH and TMA communities would raise all swan boats together. PNH and aHUS patients would see alignment, rather than separation, and a commitment to a long-term relationship. Academic trainees, researchers, and other stakeholders might start to think about these disorders in a different way and develop new ideas for studying the two based on their similar, yet unique, biologic and clinical manifestations. In a sense, this would be a patient-centric view, and one that would stand to expedite aHUS advancements. Indeed, if Ash and Dash were to combine forces, they might just be unstoppable.

Abbreviation: GPI = glycosylphosphatidylinositol

Acknowledgements: The author kindly acknowledges Dr. Richard Burwick and patient advocate Taylor Coffman for helpful discussions and thoughtful article review; aHUS alliance and Len Woodward for the opportunity to write this article.

Author contact: nburwick@uw.edu

References:

- Roth A, Maciejewski J, Nishimura J et al. Screening and diagnostic clinical algorithm for PNH: Expert consensus. Eur J Hematol 2018

- Brodsky RA. How I treat PNH. Blood 2021

- Hill A, Kelly RJ, and Hillmen P. Thrombosis in PNH Blood 2013

- Hillmen P, Elebute M, Kelly R et al. Long-term effect of the complement inhibitor eculizumab on kidney function in patients with PNH. Am J Hematol 2010

- Ravi S, Sidhu A, Kale S. The silent culprit: PNH masquerading as a cryptogenic stroke. Chest 2023.

Article No. 682