What’s new in 2022 regarding expansion in atypical HUS knowledge, and advancements for investigational drugs which may have potential as new aHUS therapeutic treatments? As with most matters, COVID-19 priorities slowed down research and initiatives specific to atypical HUS. It’s been a scattered yet productive couple of years since our last overview in 2020 regarding the aHUS pipeline and drug discovery, so we again scan this horizon while retaining our unique and independent patients’ perspective.

Our 2022 overview of aHUS drug landscape provides a broad view of key considerations and concerns, in order to provide: a snapshot of basic information on the disease and issues regarding its classification, potential drugs in pharma pipelines, and related areas which currently impede greater progress within the aHUS space. Perhaps it may surprise some that a patient advocacy group such as ours watches clinical trials and combs through research publications related to developments which even tangentially may affect advancements in atypical HUS knowledge or treatment. It shouldn’t.

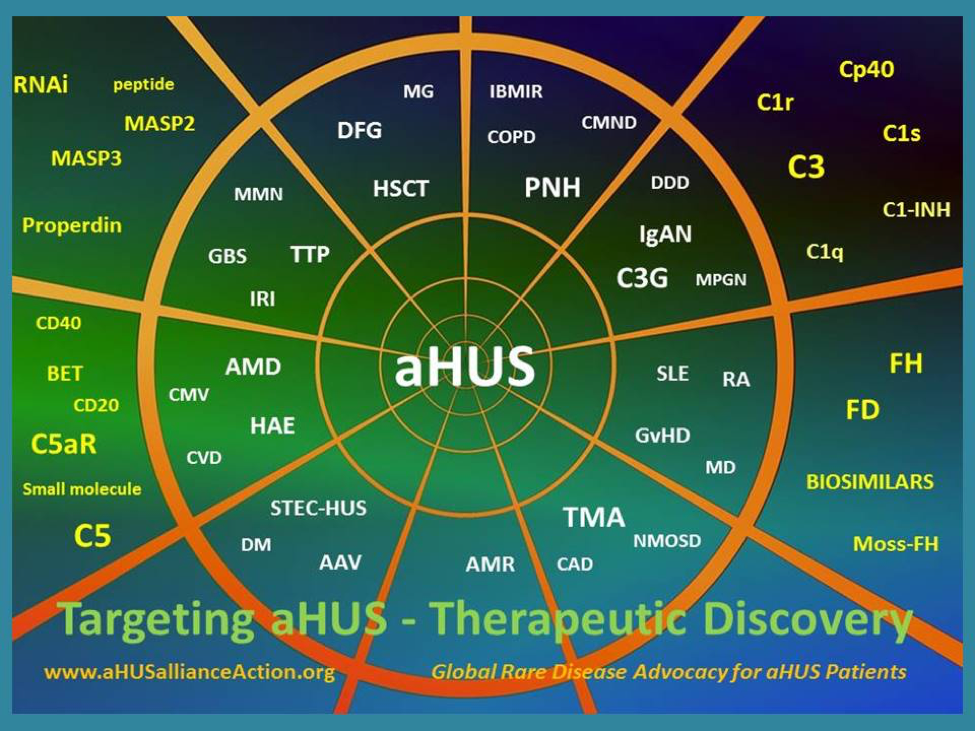

The aHUS Alliance Global Action team, as an international group of volunteers composed of actual patients and aHUS family caregivers, has keen and personal interest in watching clinical trials for potential new treatments that meet 3 criteria in addition to being safe and effective, namely: affordable treatment, which is accessible to those in all nations, and considers quality of life factors. Our ‘layman’s outlook’ presented here isn’t a literature review nor is it meant to capture investor interest regarding biotech stock – our intent is to provide advocacy-based insight into what matters to aHUS patients, their families, and medical personnel invested in treatment for this atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. To that end, we’ve created a 2022 reference chart for those interested in drug discovery, development, and clinical trials of interest in the aHUS space and which updates the landscape described in our 2020 Atypical HUS Therapeutic Drug Overview.

Of the more than 7,000 different rare diseases, only an estimated 5% have an approved treatment and we’re pleased to report that atypical HUS is among that very small group. Since our last pharma overview (and as indicated within our current chart), there’s been heightened focus on COVID-19 related thrombotic microangiopathy as well as expansion for C3 glomerulopathy (C3G) and IgA nephropathy (IgAN). There have been certain developments, as well as continuing interest areas, which are offered to provide context to better understand investigational drugs of interest to stakeholders in the aHUS space. To our knowledge, this overview is the only aHUS therapeutic drug review which blends current advancements in aHUS knowledge and drug development with the patients’ perspective to provide a comprehensive look at innovations and issues.

Horizon Scanning – Use a Telescope

People interested in atypical HUS drug development and clinical trials sometimes seem to employ a microscope, rather than a telescope to view advancements or news stories regarding aHUS. Simply put, individuals and groups who look for (or at) new knowledge or drug discovery in the aHUS space must use a wide context. Atypical HUS shares some characteristics with another rare disease, Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria (PNH) and since both eculizumab and ravulizumab were first trialed with PNH patients, no view of the aHUS drug landscape would offer a complete view without considering what’s on the horizon for drug discovery for PNH and similar clinical conditions. (July 2022, Physician’s Weekly article). A far-ranging and holistic approach is necessary to pull together the facets that realistically exist in everyday life for aHUS patients and caregivers, and for the medical professionals who diagnose and manage care.

If you put aHUS drug development under a microscope to focus on a particular investigational drug, that information does little good without understanding how it fits within the landscape of aHUS therapeutic drugs and the complex care of aHUS patients. The ‘aHUS patient journey’ has some things in common with ordinary travelers. Anyone planning their trip with a particular destination in mind must consider and navigate factors such as costs, opportunities, options, and interest points along the way. In similar fashion atypical HUS research and drug development teams, along with others in the aHUS global community, must consider a variety of facets in order to pursue pathways most likely to prove productive. So what key areas should frame the view for new aHUS knowledge and potential future therapeutic drugs in the pipeline?

What’s New on the Horizon for aHUS Therapies

After rather a stuttering start, aHUS investigational drugs are beginning to move forward with some degree of progress particularly related to options different from current IV delivery of therapeutic drugs. Patients are keenly interested in how a potential new drug would be administered (oral, subcutaneous, IV infusion), as well as the structure or basic drug type (biopharmaceutical, small molecule, biosimilar). These appear in varied combinations, such as a biopharmaceutical administered by IV infusion. A few listed on our 2022 chart are in combination with another drug(s), rather than a mono-therapy (administered as a single drug). Also important are the therapeutic targets and which pathway of the immune system is targeted (FMI: Complement System animation) The route and mechanisms may indicate how the drug addresses aspects particular aspects such as coagulation or inflammation, or may provide insight into where the immune system or complement cascade is interrupted or suppressed (which may impact patient health).

If an investigational drug is a biopharmaceutical, it usually requires more complex technology and manufacturing processes to create a therapeutic drug originating from a biologic (living organism) source. Manufacture of biologic drugs (biomanufacturing) can be particularly problematic, with potential for multiple points of failure. Creating a biopharmaceutical drug from living cells is complex and requires additional planning, investment, and specialized facilities, as well as substantial time and expertise to ‘grow’ biologic drugs. (Morrow and Felcone, 2004). These factors tend to make biologic drugs more costly to bring to market, and all countries’ rare disease policies must factor in the reality that drug price in turn drives drug access. Imagine having a biopharmaceutical that’s successful for treating a particular medical condition, and then having other companies build upon that knowledge by introducing a similar product. In a nutshell, that’s a biosimilar.

While creating a biosimilar referencing an existing biologic drug is difficult to achieve, as of 2022 we’ve begun to see movement in this area. Our pharma chart below includes information on developments in the PNH space regarding biosimilars to eculizumab (among the companies are Amgen, Biocad, Generium, and Samsung Bioepis) with interesting phrasing such as ‘lower cost’ or ‘next generation’ by some pharma pundits. Patents protect the intellectual property, and it’s no different in the field of drug development, so legally some biopharmaceuticals may be delayed in reaching market (Amgen, 2025) A quick glance at our pharma chart illustrates company acquisitions and alliances, but you’ll need to investigate and delve our links to discover that both Russian and China are becoming more involved in this drug development for complement inhibitors and rare kidney diseases

The atypical HUS community is watchful for developments regarding new methods of delivery for investigational drugs, specifically whether new therapeutics will be administered orally, or subcutaneously (SC injection, to include auto-injection device or traditional syringe and needle‘). As with any injectable biologic drug, several hurdles exist for pharma to overcome or scale up. Some concerns are patient-facing while other issues must be resolved at the outset prior to having a new drug reach the marketplace. Other issues are pharma-facing, related to mechanics of drug delivery and to structure its manufacturing and supply chains.

Subcutaneous delivery means the drug is injected under the skin by one of 3 routes: intradermal (ID), subcutaneous (SC) or intramuscular (IM) injection. Biologic drugs contain large long-chain molecules, but there’s a balance to consider between keeping a high concentration of ‘active ingredients’ and a low injection volume – not to mention viscosity of the overall therapeutic fluid to be injected (FMI Bio.org: How Drugs and Biologics Differ) Our 2022 pharma chart lists various drugs with oral delivery (to include Novartis: Iptacopan, ChemoCentryx: Avacopan, and BioCryst: BCX9930) as well as drugs with subcutaneous delivery (to include Roche: Crovalimab, or Alexion AstraZeneca Rare Disease: ravulizumab with delivery via an ‘on body injector’ noted in Dosage Forms and Strengths).

What about oral delivery, or a pill with potential to treat atypical HUS? As noted in a 2021 Frontiers in Pharmacology article, “Oral medication is the most common form of drug administration because of advantages such as convenience of drug administration via the oral route, patient preference, cost-effectiveness, and ease of large-scale manufacturing of oral dosage forms.” Small molecule drugs are quite different in composition and manufacturing processes when compared to biopharmaceuticals, since drugs like Danicopan (for PNH, Factor D: oral delivery) are more easily produced (synthesized) and so comparatively inexpensive to chemically create in a laboratory. (FMI, click HERE to read about biologics, biosimilars, and small molecule drugs). Why is an understanding of these drug types important, and why does our 2022 pharma chart contain information about other diseases?

Prior to approval as a drug to treat aHUS, eculizumab first debuted in clinical trials as a therapeutic drug for PNH patients (Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria). Given that past practice, our pharma chart has keyed in on investigational drugs for the treatment of PNH (currently 127 PNH clinical trials listed, in various stages). In the PNH clinical trial space we see the concept of an “add on therapy” with ALXN2040, or Danicopan as an “add on” for PNH patients currently using eculizumab or ravulizumab yet continuing to experience hemolysis. There’s been an uptick in progress regarding drugs which use subcutaneous (SC, also called SQ or sub-Q) delivery, commonly known as an injection. As an example of the PNH to aHUS ‘crossover’, in February 2022, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals made its foray into the aHUS space with their launch of a clinical trial for ARO-C3, which uses RNAi (ribonucleic acid interference) treatment to lower production of the complement component 3 (C3) explored as a potential therapy for PNH and other complement-mediated diseases. Of the 32 studies listed for the search term ‘atypical HUS’, only 7 are listed on ClinicalTrials.gov with the status of ‘Recruiting”. Listings can be a bit misleading since variations in key words neglect to mention all studies, such as the MASP therapeutic candidate OMS721 from Omeros, which specifies aHUS within two CT entries.

Since atypical HUS is a rare form of thrombotic microangiopathy, another focus of our 2022 pharma chart are studies related to TMA clinical trials (currently 510 TMA clinical trials listed, in various stages). There’s a bewildering jumble of aHUS terminology, which an international team of experts are sorting through via an NKF nomenclature project, but atypical HUS isn’t easily categorized. One prominent example is the DGKE mutation, which doesn’t fall within the parameters of a ‘complement mediated’ disease. In the coming year we’ll be alert to how experts resolve the issue of research and clinical trials being tagged with varied names for atypical HUS, since fragmenting information flow among terms serves no one well.

Conferences on complement therapeutics and EU medical societies were held during the summer and yielded information noted in our pharma chart below, even while new research continues to be welcomed during this third quarter of 2022. We anticipate that the annual meetings of nephrology professionals (ASN 2022: Kidney Week) and the hematology community (ASH 2022), in November and December respectively, will bring updates on promising drug candidates and the progress of studies important to aHUS disease management and treatment.

aHUS Alliance – Our 2022 Overview of Pharmaceutical Pipelines

Through the Advocacy Lens – a Fuller View of the 2022 aHUS Landscape

What broad views are advised when looking for new aHUS knowledge & potential for new therapeutic drugs to treat atypical HUS? Safe and effective drugs first need to address the prevention and development of illness and as well as disease progression, but the next key concern is establishing wider, unrestricted drug access at an affordable price point. Several factors are in play here, which need to be considered from conceptual stages through development and clinical trials for drug candidates.

Atypical HUS advocacy groups have expressed our needs, interests, and concerns in multiple projects and a continuous stream of original content articles (to include Patient-Centricity, Re-defining Patient Engagement, and Patient Reported Outcomes). Comprehensive efforts to provide information and insights included an international advocacy project developed over 4 years and launched in 2019, the aHUS Global Patients’ Research Agenda. Utilizing a 42 question poll answered by 227 international participants in 2021 on the topic of aHUS patient experiences with the diagnostic process, the aHUS Alliance Global Action team released 4 data-driven reports. In 2022 an international group of leaders within the atypical HUS community banded together to form the aHUS Community Advisory Board (CAB) to provide a collective expertise to advise research and development, clinical trials and access to effective treatments for aHUS worldwide.

Here are some highlights from these efforts, and issues raised by both aHUS families and national aHUS advocacy groups around the world.

Cost:

Many countries do not have a national rare disease policy, and some nations further may place certain restrictions on allowed drugs or medical interventions/devices. Cost can drive drug access, as nations weigh the majority of citizens’ health needs against the small numbers of patients with a rare disease. Biologic drugs versus small molecule drugs are a key feature to note when scanning the horizon for aHUS investigational drugs. Drugs that are manufactured from chemical compounds in a laboratory will reach patients at a far lower price than current biologic drugs. These ‘biopharmaceuticals’ are complex in structure manufactured from parts of plant or animal cells or from living microorganisms, so it’s an intensive and multi-step process to produce these types of drugs. (Read more HERE) Each nation decides its healthcare structure and governing rules, and unsurprisingly their focus is on providing medical care that affects large numbers of their population.

Treatment Access & Rare Disease Policies:

The definition of a rare disease varies, which makes patient numbers difficult to pin down. EURORDIS: Rare Diseases Europe estimates that there are over 6,000 different rare diseases, and consider a disease or condition as rare if it affects less than 1 in 2,000 citizens. Within this statement EURORDIS continues by noting “rare disease patients are the orphans of health systems”. According to NORD: National Organization for Rare Disorders in the USA, any disease or condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the United States is considered rare and this definition is consistent with America’s U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and National Institutes of Health (NIH). Employing this definition, GARD the Genetic and Rare Diseases program of the NIH estimates there are over 7,000 rare diseases. (Note: The aHUS Alliance website is first on the GARD list for Patient Organizations).

In a 2016 article by Karpman and Höglund on this topic mentioning eculizumab and two other nephrology drugs, they state “Government interventions and regulations may opt to withhold a life-saving drug solely due to its high price and cost-effectiveness. Processes related to drug pricing, reimbursement, and thereby availability, vary between countries, thus having implications on patient care.” and further note “Access to and costs of orphan drugs have most profound implications for patients, but also for their physicians, hospitals, insurance policies, and society at large, particularly from financial and ethical standpoints.” Less than a third of nations, especially low resource countries, currently do not have access to the two approved aHUS therapeutic drugs (eculizumab, ravulizumab). In Canada, public policy for rare disease patients and treatment continues to vary by province and in 2022 Canadians remain without a fully developed national rare disease policy when it comes to orphan drugs (CORD, July 2022).

Even in nations with access to aHUS therapeutic drugs, certain restrictions exist regarding patient subtypes (such as exclusion for dialysis) or duration of treatment. A 2021 Fierce Pharma article reported that England’s National Institutes for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended approval for ravulizumab after negotiating a discount. Around the globe but especially in low resource nations, the price point for new drugs needs early consideration by all stakeholders.

Drug Delivery:

Quality of life is a large part of this equation, but so are other facets. Consider differences for the patient and their physician when prescribing an oral drug, as opposed to intravenous therapies (IV infusion) or a self-administered injection. How does delivery method of the therapeutic agent impact their daily routine? How much patient education or caregiver training is needed? Does the drug require special handling or storage parameters which impact patient ability to easily maintain treatment protocol despite their lifestyle, work schedule, or travel plans? Drugs which are administered by IV infusion have certain limitations regarding need for the setting and qualified personnel. Location matters, since qualified people to administer an IV drug may be some distance from the patient’s home. In some cases, the small population of traveling nurses may be overwhelmed by requests for in-home care and some local IV outpatient clinics may limit services to only adult patients. Some IV drugs require special handling conditions to include drug storage and mixing parameters. Drugs administered by injection may be done at home by trained patients or their caregivers, either subcutaneous (aka a shot, SC delivery) or by a device with premeasured drug dosage. For SC delivery, patient education is vital as are dosage amounts and correctly sized delivery devices (syringe/needle or auto-injection).

Information Flow for Physicians & Patients:

People can’t make informed choices about aHUS treatment if the information flow is fragmented, and unfortunately that continues to be the case in 2022. Since its launch in 2016, the aHUS Alliance website punched above its weight with a plethora of articles related to this topic including: varied nomenclature, clinical trial barriers, inclusion of varied aHUS viewpoints, and more.

Attention needs to shift regarding two important aspects which are at work here, varied terminology and need for a multi-faceted approach. Atypical HUS as a medical condition is facing a comparable situation to that of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) which was renamed in 2013 as ‘complement 3 glomerulopathy’ (C3G) to include dense deposit disease (DDD) and C3 glomerulonephritis (C3GN). Patients and medical professionals currently find information about aHUS under diverse terminology which includes primary thrombotic microangiopathy, complement mediated disease, familial or genetic HUS, and other terms. The National Kidney Foundation established in 2021 a working group charged with sorting through the varied aHUS classification and nomenclature, although years prior we flagged this same issue (in our 2017 article aHUS and CM-TMA).

Addressing Common & Ongoing Issues

If patient groups can recognize the value of a multidisciplinary team approach regarding diagnosis and treatment, why aren’t corporate communications and scientific teams utilizing a similar avenue to update clinicians, academics, and critical care settings within hospitals? In 2022 what continues to fall into the category of ‘unmet needs’ in terms of strategies to expand enrollment in clinical trials, inclusion of patient viewpoints and concerns prior to launching initiatives, and efforts to improve aHUS patient outcomes? Here’s a synopsis of common issues for aHUS patients and the medical professionals who treat them:

- The need for creation of more effective pathways to find information about atypical HUS, to include clinical trial updates, as well as concise descriptions of disease symptoms, diagnostic guidelines, and treatment options.

- Recognition that the term ‘thrombotic microangiopathy’ occurs often throughout information flow specific to aHUS but it can be difficult to understand its context, particularly regarding multi-organ involvement.

- Clarification and classification of the wide variety among terms being used to tag information and research about atypical HUS, which currently leads to confusion and increased likelihood for lapses in knowledge.

- Improvement of pharma websites with aHUS interests to offer more accessible information about atypical HUS as a disease state, list sets of informational resources for patients and clinicians, and topically group together news releases about studies or efforts to bridge specific knowledge gaps..

- Consideration of ‘plain language overviews’ for patients regarding clinical trial updates, to include clarification of exclusion factors such as ‘Treatment Naive’. A general “Patient’s Guide to Navigating Clinical Trials’ would be helpful, to include details regarding how patients need to collaborate with their care team to enroll in a study or trial. Know that medical personnel, especially hospital intensivists, can have difficulty accessing contacts for existing clinical trials during nights or weekends.

- Since aHUS is uncommon and is difficult to diagnose, it would be beneficial to have more independent and objective resources for physicians to quickly find guidelines for differentiating TMAs.

- Investigators and pharmaceutical companies with investigational drugs in development should address drug cost and access, as well as drug target and delivery method, with early overview of these and other marketplace aspects.

This 2022 ‘state of drug discovery for aHUS potential new treatments’ has provided information about companies and therapeutic candidates which hold promise to either serve or inform drug development in the aHUS arena. Written from the perspective of patients and aHUS families, we’re on the front lines to meet the challenges that come with an aHUS diagnosis. We’ve a personal stake in finding more effective ways to improve communications, to create opportunities which can impact ‘MedEd’, with a goal to build a brighter future for people living with atypical HUS.

We challenge you to ponder your role in light of insights shared within this article, invite you to delve deeper and to share information about this rare disease, and encourage you to become engaged in finding solutions to overcome existing barriers in the aHUS arena.

Learn More

Noris M, Bresin E, Mele C, et al. Genetic Atypical Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Sep 23]. I GeneReviews® https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1367/

Atypical HUS Research & Publications – Virtual ‘library’ of over 950 aHUS-specific entries, organized by topics to include: Diagnosis, Treatment, Pregnancy, Critical Care, Genetics, Complement, TMA, and more.

aHUS Resources – An index of key articles and assets, networks & support, (Includes our Clinical Trial Watch and other series.)

aHUS Info Centre – Information and Assets (to include videos, aHUS Awareness Day campaigns, global Polls & whitepapers, French & Spanish assets, and more.

About aHUS Alliance Global Action: We’re focused on three main objectives: to promote global awareness of aHUS, to work with international aHUS research teams and investigators, and to support both existing and newly emerging national aHUS patient groups. Registered as a charitable incorporated organization (Reg No. 1167904, UK Charity Commissions, operating in the UK, USA and India), we operate the aHUS Alliance website at www.aHUSallianceAction.org on behalf of the aHUS Alliance. The aHUS Alliance Global Action group interests are non-commercial, and while our website offers news and original content related to atypical HUS we do not endorse nor provide medical opinions regarding treatment. Reach us here: Info@aHUSallianceAction.org

About the Author: Linda Burke is an aHUS family caregiver who lives in the USA and volunteers with international atypical HUS advocacy efforts through the aHUS Alliance Global Action team and the aHUS CAB. Her professional background is as a science and mathematics teacher, with a MSEd in administrative leadership.

Connect with Us: Info@aHUSallianceAction.org

Facebook: @aHUS Alliance

Twitter: @aHUSallianceAct

Atypical HUS, our dedication to Global Action: Network & Link Connections

Int’l aHUS Advocacy: National Patient Groups

aHUS Clinicians & Investigators

L Burk