Out of more than 7000 rare diseases, only an estimated 5% have an approved treatment or therapy (Rare Disease Day, FAQs). Currently eculizumab is the only drug approved to treat the rare disease atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS or atypical HUS). A drug created by Alexion Pharmaceuticals, eculizumab (brand name Soliris®) is highly effective but expensive and not widely available around the world. (Kaplan B et al, 2014. Table 4)

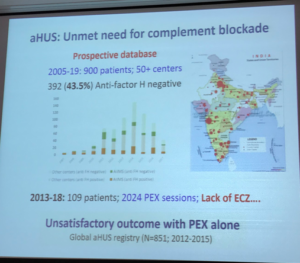

Physicians and atypical HUS families in most nations are limited to using plasma therapies such as plasma infusion (PI, usually with units of FFP or ‘fresh frozen plasma’) or therapeutic plasma exchange (aka PE, PEX, TPE, or plasmapheresis) which have been used to treat aHUS for the past several decades. Plasma therapy yields mixed results for aHUS patients (to include PI/PE non-responders). Considered as ‘supportive care’ when aHUS disease activity ramps up, rather than a treatment that prevents disease activity, plasma therapy was a mainstay of aHUS care until 2009 (Sethi SK et al, 2017) but is now considered a sub-optimal treatment.

What’s needed is a low cost drug with wide availability. Could an oral, small molecule Factor D inhibitor be the answer for aHUS patient care? Here are a few points to consider.

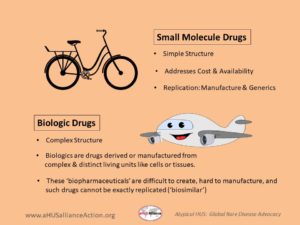

Small molecule versus a biologic drug

Conventional medicines are usually made or synthesized as chemical compounds, and are made by using specific chemicals combined in set quantities. A ‘small molecule’ drug is exactly what one might suspect, a relatively simple and small compound that drug manufacturing plants could make with relative ease. After the drug patent expires, their simple structures allow for lower cost drugs to come to market as generic drugs. (An example of a common small molecule drug is aspirin, patent date 1900).

Biologic drugs, sometimes called biopharmaceuticals, are complex in structure and are manufactured from parts of plant or animal cells or from living microrganisms. Eculizumab is classified as a monoclonal antibody (mAb), which targets complement protein C5 to interfere in formation of the ‘membrane attack complex’ (MAC), preventing red blood cell destruction (hemolysis). Ravulizumab is a next-gen biologic from the same pharma, with a similar approach to block complement. Biologic drugs are relative newcomers to the physician’s arsenal of therapeutic treatment options, but when legal drug patents expire it will not be easy to create an ‘act alike’ drug. While there may be great demand for unbranded versions of biopharmaceuticals, the original (aka ‘reference drug’) had a complex and expensive manufacturing process and therefore attempts to make a similar drug also would be costly and difficult to re-create. Companies who want to create a highly similar drug to an existing biopharmaceutical must ensure its ‘biosimilar’ will be not only safe but also effective, and additionally meet the biotech challenges of working with living cells (part of manufacturing any biologic drug, such as a biosimilar to eculizumab). Dive deeper into the topic of drug candidates of all types, to include biosimilars from Samsung Bioepis and Amgen & additional info, with our 2022 pharma update.

Consider a small molecule drug somewhat like the structure of a bicycle in that it’s a transportation mode that has multiple yet simple parts that work together to serve a distinct purpose. Keeping on theme, one might think of a biologic drug more like an airplane (e.g. ‘humanized’ mAB), whose structure has a great many more parts, with multiple components that are very complex and technology-driven.

Learn More:

- Small molecule versus biological drugs (Generics and Biosimilars Institute, GaBi Online)

- What Are “Biologics” Questions and Answers (US Food and Drug Administration)

Update: Less than a week after the aHUS Alliance published the article you are currently reading, Alexion Pharmaceuticals announced a buy out of Achillion.

Read their Oct 16, 2019 Press Release: Click HERE

Oral Small Molecule Oral Drug Candidates

A look at Achillion and BioCryst

Achillion Pharmaceuticals – an oral Factor D inhibitor

Achillion Pharmaceuticals has moved forward with ACH-4471 (danicopan) for patients with PNH and C3G. Eculizumab was initially approved to treat patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) in 2007, four years before it gained US Food and Drug Association approval as a treatment for atypical HUS. In May 2019, the company released positive interim data from its Phase 2 clinical trial using danicopan in combination with eculizumab to treat PNH. In September 2019, Achillion’s danicopan received designation within the USFDA expedited drug process as a Breakthrough Therapy for PNH (based on the May 2019 data, as opposed to data as a monotherapy). Their corporate focus includes clinical trials for danicopan as a therapeutic drug for Complement 3 Glomerulopathy (C3G), which is one of the 95% of rare diseases without any approved therapy or drug.

Following its work with ACH-4471 (danicopan), Achillion Pharmaceuticals has introduced its 2nd generation oral factor D inhibitor, ACH-5228, with target patient populations noted on its pipeline as PNH and “Additional AP Disease”. The complement system is part of the immune system activated by 3 pathways, to include the Alternative Pathway (AP). In July 2019 Achillion released a statement that its Phase 1 study of ACH-5228 has positive results with healthy volunteers. Their corporate pipeline notes a 3rd generation called the ‘7 Series’ with multiple candidates in preclinical trial with a lead to be designed in 2020.

Achillion Pharmaceuticals – Pipeline (Oct 2019)

Learn More: Click HERE to Watch a video from Achillion Pharmaceuticals.

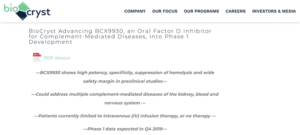

BioCryst Pharmaceuticals – an oral Factor D inhibitor

In June 2019, a BioCryst Pharmaceuticals press release announced that they’ve begun enrollment company of a Phase 1 trial for BCX9930, their oral Factor D inhibitor for the treatment of complement-mediated diseases, with initial data expected in the 4th quarter of 2019. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), C3 glomerulopathy (C3G), and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) are diseases of complement dysregulation (Wong E and Kavanagh D, 2018). An earlier press release (March 2019) noted “BCX9930 shows high potency, specificity, suppression of hemolysis and wide safety margin in preclinical studies” which could have wide application for various complement-mediated diseases which impact the kidney, blood and nervous system.

In the BioCryst press release of June 2019 regarding the preclinical profile of BCX9930, oral dosing studies noted ‘completely suppressed’ hemolysis in lab tests focused on complement activity. With preclinical in-vitro studies, BCX9930 ‘completely blocked’ C3 fragment deposition on PNH red blood cells. BioCryst plans to use results from their Phase 1 trial to inform corporate plans regarding proof of concept data in PNH patients for 2020. BioCryst noted that patients with complement-mediated diseases either have no treatments or ‘are limited to repeated intravenous infusion treatments’.

The BioCryst pipeline includes multiple compounds for three rare diseases, hereditary angioedema (HAE), complement-mediated diseases and fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP)

Why Small Molecule Drug Candidates

are a Good Fit for the aHUS space

Drug Cost drives Drug Access

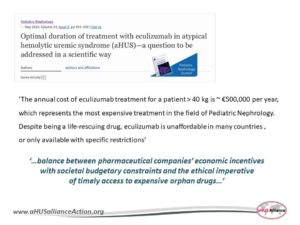

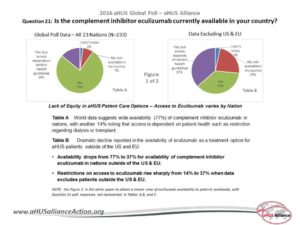

Due to the high cost of biologic drugs, many nations exclude them from approved therapies within their healthcare and drug reimbursement systems. Drug access restrictions mean that many rare disease patients in the majority of the world’s nations do not have access to so-called ‘orphan drugs’ to treat rare disease, with government policy makers citing economic analyses for per patient cost better spent on higher patient populations or nation-specific concerns (vaccines, infectious disease, etc).

While economics are a large factor in rare disease policy decisions, ethical questions regarding drug availability also come into play. Eculizumab is reportedly available in about 50 nations, which is about 25 to 30% of the world. In Canada, rare disease policy varies among its provinces resulting in only some aHUS patients having the access to eculizumab necessary obtain kidney transplants. Currently other Canadians languish on dialysis for years since aHUS can recur if not held at bay by eculizumab. For nations like the Netherlands and the UK whose citizens do have access to eculizumab, initial approval of the drug stipulated that data be gathered to determine optimal treatment parameters instead of mandating the concept of eculizumab as a lifelong drug for those with aHUS. (CUREiHUS, NL and SETSaHUS, UK).

The aHUS Alliance presented on this topic on 12 Sept 2019 at the Cleveland Clinic Children’s Rare Genetic Disease Symposium. (Click HERE to read the article)

Learn More:

- Orphan drug policies and use in pediatric nephrology. (Karpman D and Höglund P, 2017)

- aHUS Alliance: White papers (Access to aHUS Treatment and aHUS & Dialysis)

- aHUS Drug Access Model: A Global Proposal (McCullogh M and Gottlich E, 2018. Physicians’ Perspectives)

Quality of Life

Having a rare disease doesn’t just impact the patient, it affects every area of their lives and all their relationships. Family schedules and finances must flex to accommodate treatment schedules and medical appointments. Eculizumab is delivered via intravenous (IV) infusion, often in a hospital or clinic setting but sometimes at home by a skilled caregiver or other provider. Additionally, biologic drugs may need certain conditions for preparation or storage.

By contrast, oral delivery of a small molecule drug would mean greater convenience, with no travel time for treatment. Medication in pill form would not need a skilled provider to insert an IV into the patient’s vein, nor would line infections be a concern. Lifestyle adjustments and accommodations for work or school would be less needed for an oral drug versus one delivered intravenously. A Dutch study looked at patient experiences and satisfaction regarding 3 patient populations, to include aHUS patients using eculizumab Of the188 participants completing the PESaM questionnaire (Patient Experiences and Satisfaction with Medications), only 5% were diagnosed with the rare disease atypical HUS. The survey asked aHUS patients questions such as their ability to participate in society, whether they felt eculizumab influenced their energy levels, possible side effects, and fear of meningitis. Among the study’s conclusions (Kimman et al, 2019), “…patients using eculizumab generally reported less positive experiences and lower satisfaction scores in the domain ‘ease of use’ compared with the oral therapies.” It would be very informative to see a breakdown of the disease burden, to include broad socio-economic impact for individuals, patients, and healthcare systems.

The are many challenges of bringing new aHUS drugs to market. Drug policies range widely around the world, and rare disease populations by nature quite small in number. Too low a drug price, and there’s little financial incentive to take the risks involved in drug discovery and research needed to bring a drug to market. Pharmaceuticals setting too high a price will mean few nations will have the ‘per patient’ resources available, limiting the availability of even the most effective and life-transforming drugs.

Challenges in the aHUS Space

In the aHUS arena, an accurate and rapid diagnosis of the disease remains an issue due to the wide differences in how aHUS affects each patient. A logical place to focus clinical trial outreach and enrollment would be with in fields of critical care and urgent care, settings where new diagnoses often occur. Disease classification and terminology remain variable, making it difficult to follow research across a variety of medical fields such as hematology, nephrology, immunology and various specialties. A movement toward multi-disciplinary teams for thrombotic microangiopathies would be a practical connecting point for educating clinicians and conducting collaborative research efforts. The 2016 aHUS Alliance Global Poll results indicate that of the 233 adult patients and pediatric caregivers participating from 23 nations, 36% get their information from patient organizations (Q 38). Patient engagement is often mentioned in medical literature, but over one-third of aHUS patients are not involved in research simply because they don’t know how to engage (Q 29). Fragmented information flow will continue to hamper aHUS research efforts, to include drug discovery and clinical trials, until collaborative efforts join international stakeholders in working toward better networking to address gaps and promote better aHUs patient outcomes.

Learn More: Challenges in the aHUS space

Optimal management of atypical hemolytic uremic disease: challenges and solutions. Raina et al, 2019. Patients’ Perspectives, see pg 188)

Curious about possibilities for the future of aHUS drug development?

Here are a few publications

Gavriilaki et al. Complement in Thrombotic Microangiopathies: Unraveling Ariadne’s Thread Into the Labyrinth of Complement Therapeutics. Front Immunol. 2019; 10: 337

Harris et al. Developments in anti-complement therapy; from disease to clinical trial. Mol Immunol. Vol 102, Oct 2018, 89-119

Mastellos et al Clinical promise of next- generation complement therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019 Jul 19.

Wijnsma et al. Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Eculizumab, and Possibilities for an Individualized Approach to Eculizumab. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019; 58(7): 859–874